The American Dream

The first time I set foot on a baseball field, I cried.

And cried.

And cried.

At least that how my parents tell the story.

I was four years old at the time, and my mom had taken me over to one of the little ball fields near our home in Barquisimeto, Venezuela. She wanted me to play baseball, just like all the other little boys where I lived. But when we arrived, there were so many people. I was so little. I was so scared.

So I just started bawling.

“Please, take me home!” I cried, looking up at her. “I don’t want to play!” I wouldn’t even leave her side to join the other kids who were starting to run around and play catch.

She bent down and wiped away my tears. And that was it. We went home. No baseball.

Then, according to my mom, a couple of days later, I came into the kitchen when she was making dinner. This time, she was the one crying. I asked her what was wrong.

“I just really wanted you to play baseball, and to love the game,” she said.

“O.K.,” I replied. “Take me back to the field. I won’t cry anymore.”

It turned out that almost as soon as I gave baseball a chance, I did fall in love with the game. That made my mom so happy. It also brought us even closer.

I was an only child, and my mom grew up playing softball, so she was the one who taught me how to throw a ball, how to swing a bat.

She was my first coach.

I’ll never forget this one day after school. It was March 21, 1993, my sixth birthday. My mom showed up to my classroom and came in just as we were being let out for the day. I saw her give my teacher some cash, and then he handed her a baseball glove from his drawer. It was black and smooth, with yellow stitching.

“Carlos, do you like this glove?” my mother asked.

I nodded.

“Well, this is your very first glove for baseball … happy birthday!”

I didn’t even know what to say. I was so happy. My very own glove. I’d never had my own glove before, I’d always had to borrow one from other kids in the neighborhood. And even though this mitt was secondhand, my mother made sure I knew that that didn’t mean it was any less special.

“I want you to take care of this glove, Carlos,” she said. “It is going to take you where you want to go.”

Nearly every weekend, I would sit for an hour and clean that glove. I’d rub Vaseline on the dark leather so it would be shiny and soft.

Everything I learned about baseball those first few years, I learned from my mother. My dad, who worked in a factory, would often need to leave for work for a week, or a week and a half, at a time. So it was my mom who took me to my baseball games. And when I started to pitch a couple of years later, she’d come with me to help me get loose. We’d go off beside one of the fences to warm up.

She was my first catcher.

“Follow through,” she’d always tell me. I’ll never forget those words.

Follow through.

She said it over and over and over again.

When I was in middle school, I played what we called ‘winter ball’ every December. It was amazing because we played on this really nice field that was outside the city, one that had real stands and nice grass. I used to just look around at all the seats … at all the space. And when I played in our neighborhood with my friends, I’d get all these ideas — ideas inspired by that field. We didn’t live in the nicest part of the city, but we did whatever we could to feel like the pros. We used wooden planks for bats. We painted little boxes on the road for bases.

I’d always pretend I was Pedro Martínez, throwing an unhittable fastball during Game 7 of the World Series.

That was always one of the things I loved about baseball … it allowed me to dream.

Since we couldn’t always afford baseballs, we sometimes had to use tennis balls.

When my mom found out, she was furious.

“No, no, no,” she yelled. “You’re not throwing with that.”

“Why not?”

“Because the ball you’re using, it doesn’t have the same weight as a baseball,” she said. “You’re going to get hurt if you don’t use the real thing.”

Five ounces, by the way. That’s how much a baseball weighs.

Like I said, I learned a lot from my mother. And I always threw a real ball after that.

When I was in fifth grade or so, a baseball scout who was a friend of my father told him I might have a shot to reach the big leagues.

I was only 10.

I barely knew how to ride a bike.

But for whatever reason this guy really thought I had a chance to play in the U.S. So my parents and I made the decision that’d I’d sign with the scout and move in with him. His place was maybe 10 minutes away from my house, but with the schedule this guy created for me, I only got a chance to see my parents on the weekends.

I’d go to school. Then to practice. Then to the weight room. Then to bed. I did that for about three years. Then, finally, the big day arrived. My first tryout in front of MLB scouts.

“You’re still pretty young, and throwing about 81–82,” they told me. “Work hard for two years, and let’s see where you are then. We’re gonna come back and see you again.”

So I just kept putting in work.

Two years later, I got another shot to show would I could do. I remember the exact date: November 25, 2003. There were about 20 scouts and 100 other players looking to impress.

Oh, my God, I thought. How am I gonna beat out all these other kids?

I looked at my mom. She could tell I was nervous.

“Follow through,” she said. “Focus on what you do best and just … follow through.”

I threw 20 pitches that afternoon. Nothing but fastballs — all 91 or 92 mph. No changeups. Not a single curve or slider. Nothing. Only fastballs.

A few hours later, I signed a contract with the Phillies.

On March 2, 2004, I stood in front of my mother at the airport. I was about to board a flight for the U.S.

My whole family had come to see me off, but as people started to board the plane, my mother started crying. She didn’t want me to leave.

“I have to go, Mom” I told her as I hugged her. “I have to go to America.”

I was 15 then, and that was the first time I had ever been on a plane. I was completely on my own. And when I arrived in Tampa, I didn’t know what to do or what to expect. Everything was new and different.

Different country. Different language. Different rules.

I had three bags. Two had all my clothes, and the third was filled with all my baseball gear. I just thought that of course I’d need all my stuff. I was here to play baseball.

But when I got to the Phillies training facility and saw my locker for the first time, I realized I had made a mistake. Everything was already there waiting for me — shirts, uniforms, equipment. There were three brand-new Wilson gloves. And everything had my name on it, and the MLB logo on it, too!

I walked over to a trash can, threw out all my old stuff and got to work.

And, you know what? The baseball stuff was the easiest part of it all. Baseball I knew how to do — the running, the throwing, the competing. All of that, I could do.

The hardest part was the language.

I didn’t know any English, so I couldn’t really to speak to anyone. I didn’t even talk to my mom until a week after I arrived because I didn’t know how to get a calling card — or how to ask anybody for help getting one. When I finally figured it out, I called her right away and told her everything — about all the new cars I had seen on the roads, about my teammates, about my pitching. I told her how much I missed home, but how happy I was to be in the States … to be playing baseball. To be living out my dream in America.

During my first spring training, I ate Domino’s pizza every day for dinner.

I’m not exaggerating. I had Domino’s every … single … day. It was the only thing I knew how to order.

So for 90 days, I ate pizza. I ordered it so much that the Domino’s near our facility ended up giving me one month of free pizza as a reward for being their best customer.

Aside from eating pizza and playing baseball, I didn’t do very much, though. For those first few years in the U.S., I didn’t really talk to many of my teammates. Not because I didn’t want to, but because I didn’t know how.

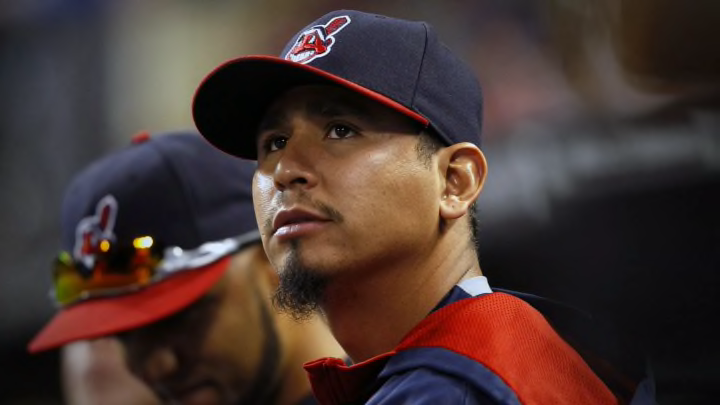

In 2009, I decided it was time to change that. The Phillies had traded me to the Indians in July, and I wanted to get better with the media. I wanted to be able to talk to my new teammates. There was also the fact that I had recently gotten married and my wife and I were looking forward to raising our children.

I wanted America to really feel like home. Because it was becoming my home.

Language classes never worked for me because I had always been too busy with baseball. So I decided to learn English by talking and reading with the people around me.

There are plenty of guys in the majors who have gone through the same thing. And another Venezuelan player told me that to start learning English, I needed to begin with a couple of phrases.

“I see….”

“I will….”

“I can….”

So I started there. And I told my teammates to let me know if I got something wrong.

Little by little, I improved. I’d pick up phrases here and there. And there were so many phrases that American ballplayers used all the time.

“Good job!”

“Great work!”

I started to speak to the media more. I talked to my teammates more. And after a while, I could even help my kids with their schoolwork. I was becoming part of a community in Cleveland. But there was still something else that I needed to do.

I wanted to become a U.S. citizen.

Last spring, I worked up my citizenship application and filled out a bunch of forms. I went to an immigration services office to finalize my paperwork, and as I left was given a little booklet that has 100 facts about the United States — things like who the first president was, and when the Declaration of Independence was signed, and the names of the three branches of the U.S. government.

I was also given something else. The date that I’d be taking my citizenship exam: August 4, 2016.

My wife became a citizen a few years ago and I had helped her study, so I had read most of the booklet already. But I still carried it around with me everywhere I went last summer. I had been in America for more than 10 years, and had traveled all over the country, but there was so much I didn’t know. It was wonderful to really feel like I was becoming a part of a country by learning about its history.

My teammates enjoyed the experience, too. A lot of them would quiz me, especially Jason Kipnis. On our team flights, I’d hand him the book and he’d sit across from me and run through some of the facts.

“What do we call the first 10 amendments to the Constitution?”

The Bill of Rights.

“How many justices are on the Supreme Court?”

Nine.

Most of the guys were really surprised by how much I needed to know, and how much I had to study.

I really worked at it. I studied hard.

Then, when August 4 rolled around, I flew to Florida, where I had registered to take the exam. When I arrived at the immigration office, I was so nervous. My hands were even trembling a little bit.

But I felt like I was ready.

When you take the citizenship test, you have to answer three questions out loud in English, read three sentences and write down three sentences.

I had studied that little booklet so much that before the woman could even finish the questions, I already knew the answers.

“The Federalist Papers supported the passage of the U.S. Constitution. Name one of the writers who—”

“James Madison!”

Like I said: I was ready.

And I still remember one of the sentences that I had to write out.

“California has the most people.”

After 30 minutes, I was done. It seemed like such a short time for something so important. But really, that moment had been 12 years in the making — from my first plane ride, to all those nights eating pizza, to meeting my wife, to having kids.

When I first arrived in the U.S., I was a shy 16 year-old kid who missed his mother and spoke no English. Now, I was a husband and a father, who had been playing in the major leagues for nearly a decade.

And in a few minutes, I would become a U.S. citizen.

The people at the immigration office told me that they could swear me in that day, before my flight back to Cleveland at 3 p.m. I went into a separate room, raised my hand and recited the Oath of Allegiance. Then I signed a piece of paper.

“Congratulations on becoming a U.S. citizen, Mr. Carrasco,” they said, as they handed it back to me.

I took my certificate, and I went to the airport. You couldn’t tell there was anything different just by looking at me. I was still Carlos.

But now, finally, I was also an American.

I called my mom in Venezuela on the way to the airport and told her I had passed. She started screaming right away — she and my dad were so happy for me.

“Congratulations!” she said. “You’re an American now.”

I thought about my mother a lot that day. What it had taken for her to let me go live with that scout when I was only 10 years old. What it had taken for her to let her only son leave for a different country at 16 years old.

It has not been easy being away from her. I try to visit her as often as I can, and I still have that first glove she bought me for my sixth birthday. It still looks like it did the day I got it: smooth and black, the yellow stitching just as bright.

And of course, I think of her every time I’m standing on the mound in America.

Follow through, Carlos. Follow through.

The first road games we played after I became an American citizen were in New York and Washington, D.C. I’d been in America for 12 years. I’d flown in and out of those cities plenty of times before.

But this time, it felt different.

I looked out the window as we landed in Washington. The airport is beside the historic monuments. So you fly right over them before you land. I could see the Lincoln Memorial, the U.S. Capitol, the Washington Monument. The history behind them was my history now, too.

And then I stood out on the field at Nationals Park. The national anthem began to play and we all turned towards the flag. I’d heard the anthem before. I’ve looked at the U.S. flag for 162 games every season.

But ever since I became a U.S. citizen looking at the flag has meant something more.

Home.

It’s my anthem and my flag now, too.

When I got to my locker after the last game of our series in Washington, my clothes were gone. My teammates had hung up an Uncle Sam costume for me to wear on the flight home instead.

“Welcome to America!” they all cheered at me.

I wore that outfit on the bus, and then on the plane ride back to Ohio. I loved it!

The guys are so happy for me, and it’s been great to share this with them. There’s just this spirit here — from my teammates, to the people in the front office, to our trainers. It’s unbelievable. We’ve gone through so much together on the field, of course. But they’ve had an even bigger impact on my life because of everything that has happened off the field. Every day they helped me learned English. They are the ones who really helped me become an American.

Then in September I broke a bone in my right hand. My season was over. But I did get to be there for my teammates. A lot of people wrote them off. They wrote off the guys who had taken the time to quiz me during flights — even after games. They wrote off the guys who had written down the past, present and future tenses of words on pieces of paper for me.

I didn’t get that perfect ending of getting to pitch in the World Series. And we didn’t get the trophy at the end of it. But that dream — our dream — keeps going.

And as far as my American dream?

I used to think that it was just coming over here and getting the opportunity to play baseball.

But it’s more than just standing out on the mound. Or starting my first major league season as an American. It’s looking up into the stands at my wife and kids. It’s looking over at my teammates. It’s looking around at our fans in Cleveland.

And knowing that I’m home.