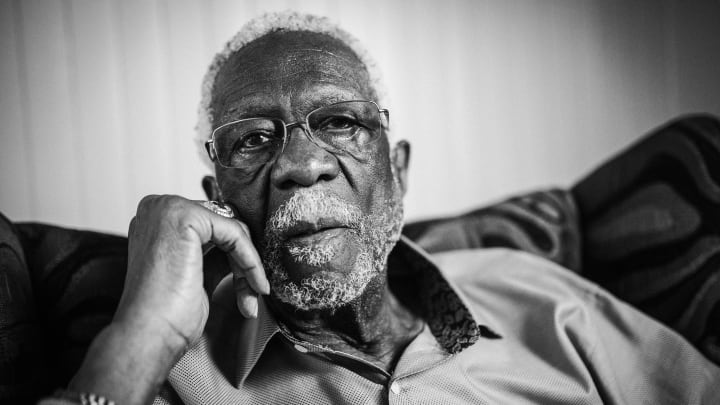

Racism Is Not a Historical Footnote

I once interviewed Lester Maddox on my television show. It was 1969 and he was well known at the time as a Southern segregationist and former chicken restaurateur turned politician. Maddox and I had diametrically opposing perspectives. He got out of the restaurant business after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 passed so that he wouldn’t have to serve Black people, while I once refused to play an exhibition game after a restaurant refused to serve me or my Black teammates.

Maddox made a show out of his refusal to integrate his restaurant. He waved axe handles and guns at peaceful protesters and argued, loudly, that being forced to serve Black people encroached on his freedom. He closed his restaurant in Atlanta, ran for governor of Georgia, and won.

So why would I give a platform to an individual who held such racist beliefs? First, part of freedom is allowing everyone — even the most hateful people — to speak. And second, doing so also exposes how a person comes to hold such beliefs. Now, Lester Maddox wasn’t exactly an intellectual giant, so I doubt he would’ve been able to question the culture he had been born into if he tried, but having him on my show exposed him for the fool he was and might have also given other people some things to think about regarding the plausibility of “separate but equal.”

Even though that moment has long since passed, I’m struck by how similar it felt to the moment I’m living through now. In 2020, Black and Brown people are still fighting for justice, racists still hold the highest offices in the land, and kids today still grow up with cultural norms that aren’t different enough from the ones that Lester Maddox grew up with.

In 2020, Black and Brown people are still fighting for justice.

Now, when I say Black and Brown people are still fighting for justice 50 years after I interviewed a prominent segregationist — “an old country boy” who ran for political office on a platform of hate and won[1]— I don’t mean to sound surprised. I’m not. White people are surprised by that. In fact, I find that white people are often surprised that racial injustice still exists outside of a few “bad apples.” This surprise is particularly dangerous because racial injustice is rampant throughout every sector of American society, from education to health care to sports, and the fact that this remains surprising to many reveals exactly how different Black and white people’s experiences of life in America are.

I grew up in Monroe, Louisiana, in the 1930s and early 1940s in a family that managed to laugh despite the racial terror that surrounded us. There was the night the Klan came for my grandpa. He knew they were coming, so he had taken his family someplace safe and then sat at his house waiting for the Klan to arrive. He never said anything about what it felt like to wait, alone in the dark, for men intent on murdering him, but it must’ve been equal parts terrifying and infuriating. When they got there, someone fired a shot, so my grandpa went to get his shotgun so he could shoot back. Grandpa started firing and kept reloading until the Klansmen left. The story was told and retold throughout the community, the rare story of a Black man standing up to injustice without facing brutal repercussions. Everyone would laugh when they reached the point in the story when the KKK left, running. That moment was a moment of sheer relief, even in the telling — but we all knew they could come back the next day.

He never said anything about what it felt like to wait, alone in the dark, for men intent on murdering him, but it must’ve been equal parts terrifying and infuriating.

One time, my dad ran out of gas in his work truck at the end of the day and had to walk home. While he was walking on the road, a couple of white men pulled up next to him in a car and asked, “Boy, can you run?” My father said nothing and kept walking. One of the men waved a gun in the air before repeating the question. My father started running. A bullet whizzed by. My father dove off the road into the ditch to keep from getting killed. When he would tell the story later, he’d say that he yelled at the snakes to move over, which always got a big laugh.

There were some stories no one could laugh about, though — stories about Black men disappearing. That was how lynching happened in those days, quietly, without so much as a line in the newspaper. Black people were too scared to ask publicly what had happened to the men who went missing, although they speculated at home plenty.

All of this might seem like ancient history, with no bearing on today. After all, these are stories from my early childhood, stories that are 80 years old. But in terms of time, 80 years is only a generation or two. Black kids today don’t grow up worried the Klan will kill them in the middle of the night — they worry the police will. The effects of racial terror perpetrated over hundreds of years don’t disappear simply because America wills them to. Yet all is not hopeless. There are ways to make them disappear. They disappear with national reckoning, with an examination of our cultural norms and our power structures, with the dismantling and rebuilding of our institutions, and by ending voter suppression so that everyone can vote for change from the bottom to the top of the ballot. In 1969, Black and Brown folks were fighting against social injustices that are no less pervasive today, the mode of delivery has just changed. They are easy to see if you only look, particularly in politics.

When asked about integration for an article published in Esquire in October 1967, Maddox said, with a Southern drawl, “When the government tried to force my customers to sit next to Negroes I got mad. We don’t cotton to that down here. I’m a peaceful man and I always treated my colored help fair with due respect and a decent wage. But I’m not going to live next door, no sir.”[2] In other words, Maddox had nothing against Black people, as long as they were subservient to white people and stayed in their neighborhood. This sentiment is alive and well today. In July 2020, for example, Donald Trump, a New York businessman turned politician tweeted about ending a government program put in place to combat racial segregation in suburban housing: “I am happy to inform all of the people living their Suburban Lifestyle Dream that you will no longer have to be bothered or financially hurt by having low income housing built in your neighborhood….” Of course, when he said “low income housing” would be built in “your neighborhood” he meant “Black and Brown people” will move to the suburbs, which are still mostly white due to redlining and economic disparities. Despite being separated by 53 years, the only substantial difference between the two men’s statements is their accents.

Real change takes time — lots of it. This is infuriating but not surprising when considered in terms of foundations. America is a country of contradictions because of its foundation. On the one hand, there’s the idea of what America is supposed to be, and on the other, what America really is. America claims to be the land of the free, but it was founded on indigenous genocide and built on slavery. As a result of this discordant origin, America is a country at odds with its past.

As long as large swaths of Americans regard slavery, Jim Crow and racism as historical footnotes — missteps long since corrected — there is no way to move past racism. Fifty-three years won’t do it, and 153 years won’t do it. It’s like apologizing for something without knowing what you’re apologizing for — no real understanding comes of it. If America doesn’t reckon with the past, divisions will only worsen.

Real change takes time — lots of it.

The funny thing about the past, though, is that it’s never really gone. In some ways, my entire life was built on the foundation built by my parents. This is not unique to me. For better or worse, your life was also built on its foundations, whatever they were. America is no different. Its foundations are readily apparent, if we only look.

They imbue everything, from who we honor in monuments and statues, to the history we teach in classrooms, to the mascots we choose for our sports teams. Recently, Confederate statues have been toppled, some purposefully, and some by force. I remember when a monument honoring Confederate soldiers was built in 1963 in Boston, even though we weren’t in the South, and even though it honored people who had fought for slavery, and even though it had been 100 years since Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. That monument was built in response to desegregation. It was built by the Daughters of the Confederacy, far from the South, as a reminder of the Grand Old South. It was nostalgic of a time when Black people were enslaved, when there was pride in the fight against freedom, and it remains a clear example of how the heartbeat of the past thumps on into the present.

Nowhere is this more readily seen than in education. Education is one of the most powerful tools we have in the fight against racism because it is foundational in the formation of an entire generation’s beliefs. Kids learn their ABCs, but also about America’s history, and American culture. When I was a kid, I came across a passage in an American history book that still sears my soul. It said that slaves were better off living as slaves than they were living free in Africa. It infuriated me even as a child. Life without freedom is no life at all.

Kids are unlikely to come across a passage so explicitly racist today, but they experience more subtle forms of racism, such as Black History lessons, which are taught as adjacent to American history, rather than an integral part of it. In order to eradicate racism, we must provide our children with an education that includes all American history and that examines how that history continues to shape our institutions, beliefs and culture.

In order to eradicate racism, we must provide our children with an education that includes all American history and that examines how that history continues to shape our institutions, beliefs and culture.

The icons we choose for sports mascots also say a lot about American culture. One of the most ubiquitous mascots is the American Indian, typically pictured as a racist caricature and sometimes completed with a racial slur. This year the Washington Redskins finally decided to change their name after years of refusing to, despite the repeated requests of indigenous peoples and social justice advocacy groups. It shouldn’t require advocacy or social pressure to recognize that a racial slur is not an acceptable team name. We teach our children that name calling is not O.K. because it is disrespectful and hurtful. Team names and mascots are no exception, and the fact that so many racist names and mascots still exist is indicative of how deeply embedded racism is in American culture.

Racism in America doesn’t simply affect Black and Brown people. It seeps into American institutions, shows, music, news, sports and minds. We can’t change America’s foundation, but we can reckon with it. Or, we can continue (as we have for hundreds of years) claiming to be the land of the free, when it’s clear that the sentiment only applies to white people.

America is not the land of the free when Black people have to worry that they will be murdered in their sleep like Breonna Taylor. America is not the land of the free when Black people have to worry that a police officer will kneel on their necks for eight minutes and 46 seconds like they did to George Floyd, until the life was choked out of him. America is not the land of the free when Black children can’t play with a toy gun without fear of being murdered like Tamir Rice. America is not the land of the free when Black people have to worry about being hunted down and murdered while out on a jog like Ahmaud Arbery. America is not the land of the free when Black people have to worry about being shot in the back in front of their children like Jacob Blake. America is not the land of the free when Black people’s murderers always go free.

Without justice for all, none of us are free.

[1] Notably, Maddox didn't win the majority vote, but was appointed governor by the State Legislature after it was put to. vote. He won the legislative vote, 182 to 66.

[2] The original quote was written phonetically and standardized here.