Betting on Myself

We’ve all seen the wildly popular movie Jerry Maguire. What’s not to love? Jerry’s got it all: a shiny gig at a prestigious sports agency, elite clients that command respect and a beautiful fiancée. He appears to have a dream life, until his career comes crashing down and he loses everything.

Everything except for one client: Rod Tidwell, an aging-but-talented wide receiver for the Arizona Cardinals who’s not exactly the easiest guy to please. Though the relationship between Jerry and Rod is at many times trying and turbulent, the two end the movie with a tearful embrace in front of the media, showing how their bond has progressed from a traditional one that is all about business, to a personal one that is close and heartfelt.

If you haven’t seen the classic flick — spoiler alert! — it concludes with a touching scene in which Jerry secures a deal for Rod to finish his legendary football career with the Arizona Cardinals.

I hate that movie.

Now let me tell you why I hate that movie. I love Tom Cruise, but Jerry Maguire represents one of the wildest misconceptions in the sports world: that athletes need agents. This movie insinuates that athletes need someone else to “show them the money” because they can’t get out there and get the money themselves. I hate that.

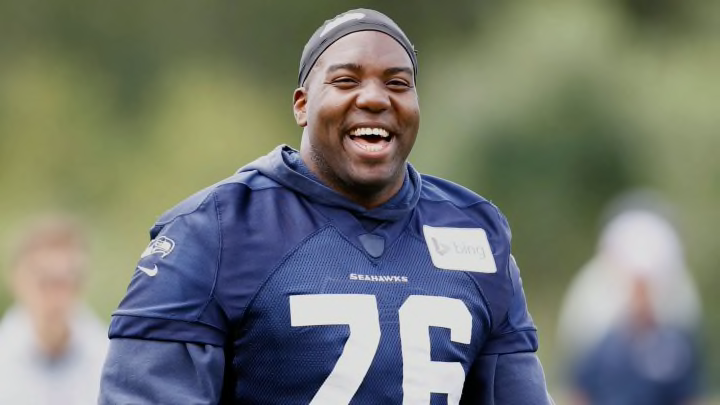

You see, prior to being selected sixth overall by the Seattle Seahawks in the 2010 NFL Draft, the Jerry Maguires from some of the biggest agencies in the world courted me. From seemingly every avenue possible, sports agents found me and gave their best pitch. I was promised it all — the possibility of securing endorsements and show deals, appearing in Coca Cola commercials and wearing tailored suits to the best parties in the world. Not to mention, of course, a lucrative contract.

As a 21-year-old offensive tackle out of Stillwater’s Oklahoma State University, I knew I’d made it big time. I understood that my life would change forever. I’d no longer be that kid from humble beginnings in Houston, Texas, but a personality in the greatest league in the world. I could set up my family, my finances and my legacy forever. All I had to do was find someone to show me the money. In essence, I was under the impression that selecting an agent was the precursor to my wildest dreams.

I weighed my options — noting the factors most important to me — and made my decision. Soon after, I sat with my new agent to discuss the terms of the deal. He told me that the standard rate, which is set by the National Football League, was 3 percent. I asked to pay 2.5 percent, and without much pushback, my agent agreed.

From that moment, I knew I possessed an intangible factor in the relationship that I’d never considered: leverage.

The sheer length and complexity of player contracts means that many agents are lawyers or, at the very least, have some sort of background in contract law. Agents are expected to be savvy about not only the game, but about finance, business management and risk analysis. They’re also expected to be marketing gurus and sharks when it comes to securing endorsements. Is it really possible for one person to be a true expert in so many fields?

And what does it look like when that expertise is spread across, say, 20 clients? My agent wasn’t only promising me a lucrative contract and then some. He was promising every other player he was representing a lucrative contract and then some. How do agents manage so many people, especially if they’re promising each one of us the same deals? What about the inevitable conflict of interest — for both the agent and the athlete — if an agent represents two players on the same team?

The fact of the matter is that even if the agent-player relationship is a close, heartfelt, personal one, it’s still founded on one thing: money.

Did a 2.5 percent agent fee really make sense in relation to the amount of work that was being done? Did it make sense in relation to the amount — and caliber — of those commercials, endorsements, show deals, suits and parties that were or weren’t delivered? Did I, entering the final year of my rookie contract and what I believe will be the prime of my career, really need someone else to tell me my worth and not only “find me a deal,” but take a cut of it?

No.

So, before I became a free agent, I decided to free my agent.

Now, I’m merely speaking from the heart because I witnessed — and continue to witness — this truth not only in my own situation, but through other players as well. I see guys who believe they need representation because they merely haven’t considered an alternative.

Granted, there are plenty of guys who didn’t take the same route as I did; guys who aren’t in the same position as me. There are undrafted free agents and “journeymen” who constantly move from team to team. They spend the majority of their careers on the practice squad with the slim possibility of making a team before it’s time to retire. I applaud their efforts; in so many ways they’re the backbone of the league.

And for guys like that, agents are useful. They have relationships with general managers to get workouts and start up initial conversations. But in my opinion, that expertise doesn’t warrant a relationship that leads a player to believe he’s inadequate without representation.

And because I know I’m more than adequate without representation, I’m betting on myself.

I know my worth. I can look at the market and go directly to a team without an agent and tell that team my worth. And I can do so with confidence because I’ve done my research, I’ve educated myself and I’ve questioned the answers I’ve been given. And when it comes to reviewing the details of my next deal, I’ll hire an expert — a lawyer or a sports attorney who understands the dynamic of football contracts — to read the paperwork. I’ll negotiate a one-time flat fee that isn’t dependent on the size of my salary.

You see, there’s a new sort of athlete, and he’s not just an athlete. He’s a businessman and a living brand, a la Magic Johnson or LeBron James. He’s a player who represents himself because he not only understands the market and his own personal value, but has the self-assurance and financial know-how to do so, too.

Every athlete has the ability to be free of his or her agent. It all comes down to being willing to bet on yourself.

So, fellow athletes, I encourage you to do your research. Educate yourself. Question the answers. And take ownership of your career and your livelihood.