Something Bigger

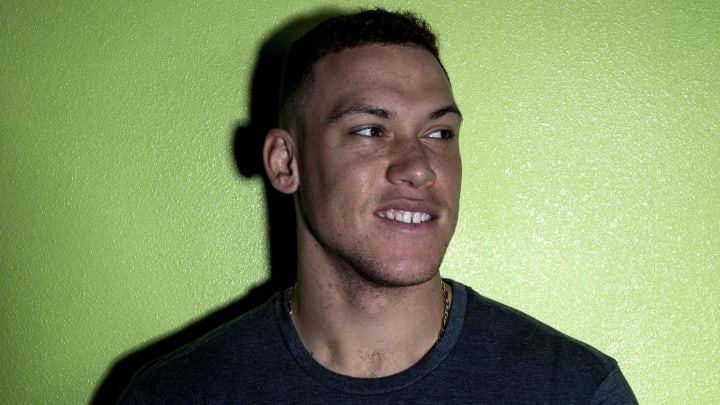

Sharpie and The Players’ Tribune have partnered to create a series around Uncap the Possibilities, which shows how a Sharpie gives people the power to unleash their imaginations — and to express how they’d like the world to be. Here, Aaron Rodgers explains the origins of his passion for working with veterans, which led him to team up with the Wounded Warrior Project.

Afew years ago, I was in Carlsbad, California, getting fitted for new golf clubs. Just before I went out to the driving range, somebody told me that I would be sharing the range that day.

“Great,” I said. “Who’s coming?”

“The Wounded Warriors.”

I’ve always had an appreciation for the men and women who serve in our military. My grandfather, Edward Rodgers, was active duty in the Air Force in the Second World War. His plane was shot down and he was a prisoner of war for nine months. He came home with a Purple Heart and a Silver Star.

He passed away in 1996. I had just turned 13, so I never really got a chance to spend time with him on an intellectual level, when I would have been able to understand the gravity of the stories he told or the sacrifices he and others had made while they served. But from what I know, I think that in his opinion, serving was one of the greatest achievements of his life. And I know that my family has always had a strong sense of pride about his service.

So as far back as I can remember, an appreciation for the military is something that’s always been part of me.

It’s one of the reasons why I was so excited when I found out I would be sharing the range with the Wounded Warriors that day, and it turned out to be an incredible experience.

I remember standing there, watching them hit balls. One warrior was a double-leg amputee. Others had lost an arm, or an eye, or were overcoming various other disabilities and challenges. And while I found myself marveling at their ability to hit the ball, what really struck me was the joy that these men and women took in getting back to doing something they had loved to do before they were in the service — before their injuries.

What I took from that experience was the idea of perspective. How special the little things are — simple things, like the ability to hit a golf ball.

Things many of us take for granted.

There are a lot of folks out there who have given their lives or their livelihood for a cause that they believe is bigger than they are.

I think back to 2004, when I was still playing at Cal. We were in San Diego for the Holiday Bowl and some of my teammates and I visited a military hospital there and met with men and women who had been injured in Iraq and Afghanistan. Some had suffered gunshot wounds. Others had been caught in grenade explosions.

I obviously admired them for their courage and sacrifice. But what really struck me was that despite their injuries, some of them couldn’t wait to get back to active duty. They were pleading with their doctors to help them so they could rejoin their units and continue fighting.

The strength of the bond they had with their fellow soldiers was something that really stuck with me. I was just amazed by the selflessness they displayed and their complete devotion to — once again — something bigger than themselves.

The idea of being a part of something much bigger than yourself is something I have always gravitated toward. Football is the ultimate team sport. That’s one of the things I love most about it. And I think that everybody — regardless of their faith, background or whatever — is searching for something like that.

Something bigger than themselves that they can give themselves completely to.

When the opportunity presented itself to partner with the Wounded Warrior Project, for me it was a no-brainer.

What the WWP tries to do for veterans is give them the opportunity to live life on their own terms, take control of the narrative of their lives and allow them to get back to doing the things they enjoy doing. With all the stuff some of these veterans have to deal with — from injuries, to post-traumatic stress disorder, to potential disability, to getting back on their feet and getting a job and getting assimilated back into society — the WWP helps them achieve it.

I play in a celebrity golf tournament in Tahoe every year, and a couple of years ago I had the opportunity to play with Chad Pfeifer, a veteran who had his left leg amputated above the knee after the vehicle he was driving hit a roadside bomb in Iraq. He learned how to play golf in 2007 while he was rehabbing at an Army hospital.

Today, he’s a three-time Warrior Open champion, which is an annual tournament for veterans who have been injured in combat.

Getting to play golf with Chad for a round was fantastic. He’s a great golfer and an even better human being. Just sharing the course with him was truly inspiring.

There are a lot of Chad Pfeifers out there, I think — people who have gone through a terrible trauma, who have made such an incredible sacrifice for our country, and now they’re back out in the world doing something they love and enjoying life.

I saw a number of them that day on the driving range in Carlsbad.

But there are countless others who are struggling to assimilate back into society. They’re having difficulty finding jobs, or they’re suffering from debilitating post-traumatic stress disorder.

To me, when it comes to taking care of our veterans and helping them not just assimilate back into society, but to actually thrive, I don’t think there’s any limit to what we can and should do.

Veterans make the ultimate sacrifice so the rest of us can enjoy the freedoms we so often take for granted. The least we can do is work to create an environment in which they can come back after serving and experience those same freedoms to the fullest and live their lives on their own terms.

I think that’s a great way to show our appreciation.