Making a Homicide

I had all their names on a sheet of paper. Written in pencil. Every single respected streetballer in New York City.

One by one, I was going to destroy them.

I was going to dominate every last one of them, until they couldn’t look me in the fucking eye. When I had them in my pocket, only then would they be crossed off the list.

This was before streetball went mainstream. Before kids were doing crossovers in their driveway and screaming “Hot Sizzle!” We weren’t chasing magazine covers. The only currency was respect. So that’s what I tried to get.

Everyone knows that there are commentators at these streetball games, and they’ll give you a name based on your style of play. These nicknames are usually just based off of your first few plays at a big tournament. Trust me, you want a good nickname. When I started my first game, I got a nickname early.

“He’s workin’ hard! The Hard Worker!”

Whack. Fortunately, nicknames tend to evolve a little bit.

“Naw that ain’t gonna fit him. We need him a better name.”

The game keeps going, and they’re shouting out other names. I started getting a little excited because I’m balling and these names keep getting more vicious.

“The Killa!”

“The Murderer!”

“Naw, what’s his name?! What’s his name?!”

Then somebody off to the side whispers “Corey Williams.”

“A’ight, we gonna call him C-Murda!”

“Naw, we gonna call him C-Homicide!”

I don’t think I need to show you a highlight reel from the game. The name says it all.

And after my second game, they dropped the C.

The process was complete and now I was a felony on the court.

I was Homicide.

A few years back, we were playing a game in Baltimore.

Now, New York hates Baltimore. Baltimore despises New York. We were in this tiny ass gym and the game starts late. As far as crowd control goes, there is none. The huge crowd of people outside the gym got impatient and kicked in the door in. Within a few seconds the court was surrounded — like people right up on the sidelines. And in their sort of country accent they’re yelling things like, “Fuck y’all, you New York motherfuckers!” and, “You ain’t going to make it out this gym!”

So the game starts and my man Future is taking the ball out. Behind our bench, are at least, I swear to God, like 100 Bloods. Bloods are gang members. Baltimore Bloods are probably some of the most dangerous gang members. And these guys are all dressed in camo, with scarves — so you can’t see they faces — and red hats. Bad fucking news. So I’m like, “Let’s just play ball and get the fuck outta this gym.”

During the game, Future is inbounding the ball and someone on the sidelines starts screaming, “Future, you ain’t shit! You ain’t shit!” And then he pulls Future’s shorts down.

The whole New York team just froze.

And I’m praying like, Please, just pull your shorts up, pass the ball inbounds and let’s stay alive. If anything popped off, we were dead. Fortunately, Future’s a smart man. He just casually pulled up his shorts and shook it off like it wasn’t nothing. And we made it to the end of the game and got the hell up out of there.

And no, we didn’t win.

No shot we were dumb enough to win that game. Know when to hold ’em, know when to fold ’em.

Before I became a murderer on the basketball court, I was just a Jamaican kid in the Bronx named Carey.

I hated that damn name.

I used to get teased all the time about it when I was in elementary school. Kids are the worst, man. They’d say shit like, “Carey my book bag,” and on the court they’d tell me it was their ball because I’d “Carey-d.” As if I ever turned the fucking ball over during a basketball game at that age. No shot. My frustration kind of built up, and on the first day of middle school, when the teacher took attendance and called my name, I told her there’d been a mistake. My name was actually Corey, not Carey. And that name stuck until I became Homicide. It was a proud moment for a young legend in the making.

I first got interested in streetball when my older bro George played for an AAU program in the city at Riverside Church. I’d always try to tag along to watch his games. Watching that team play was really how I fell in love with the game. I was immediately drawn to the toughness, but also the flow. When played at a high level, streetball is really art. Your game is an expression of yourself. And I fell hard for the game. I started daydreaming about it all the time. I knew this was something that I really wanted to become great at.

Due to poor grades in middle school, my mom wanted to get me into a private school because she felt that I needed discipline. She wasn’t wrong. So she took me to a small, all-boys Catholic school in Harlem called Rice. We met with the dean there, a man named Dr. Walkerman. At first he wasn’t convinced that I belonged due to my poor grades. But my mom begged him to let me in, to just give me a chance. The school decided to give me a shot, and it honestly changed my life.

It turned out that being at an all-boys school, while incredibly frustrating for obvious reasons, was exactly what I needed. All that extra energy I had went to basketball. That’s how it was with pretty much all my classmates, too. I was in a class of 93 kids, and pretty much all of us could ball. Rice was notorious for producing talent for D-I programs. I went there at the same time as the great Felipe Lopez, who was on the cover of Sports Illustrated as a senior.

Being in that kind of disciplined environment got my head right, but my body still took some time to catch up. I was a late bloomer, so by the time I graduated there weren’t any scholarship offers waiting for me. I decided to go to a juco in Kansas City called Penn Valley C.C. I flourished there, winning a D-II national championship and being named a Juco first-team All-America as a sophomore. From Penn Valley I earned a scholarship to play at Alabama State.

Basketball was all I wanted to do, but at State I wasn’t really getting heavy minutes or putting up numbers. I knew that if I wanted to keep my career going I had to get creative.

My mom’s only wish for me was to get a degree. She’d tell me, “Do whatever you want to do. Follow your dreams. Just graduate!” So I did just that, earning a criminal justice degree in 2000. But that was entirely for her. I swore to myself that I’d never use it. I was going to play ball.

I was flipping through a magazine one day, and I stumbled across this feature about streetballers in New York. It looked O.K. There weren’t a lot of guys making money from it, but there were a few. It was clear the college route wasn’t going to do it for me, so I figured I should get back to my roots on the playground. But I knew that if I wanted to get paid to play basketball, I needed to create a name for myself from scratch.

So I got started on that.

I went into it with a certain goal in mind. I didn’t necessarily want to win games I wanted to turn heads. And I was going to do that through volume. You see, on the playground there’s no coach who will take you out for turning the ball over. It’s style over substance. So to build my rep, I put together a team of solid players who would give me the ball. And because it was my team, if I got the ball 30 times you better believe I was going to shoot it 30 times. And with that freedom, I started getting a lot of buckets. You could block my shot three or four times, but I wasn’t walking to the bench. You didn’t get off easy. I was going to come right the fuck back at you until I got mine.

Now in regular ball, all people talk about is championships. That’s real nice, but that wasn’t my mentality. Like, who gives a shit if you win a street ball championship? Nobody remembers that. But they sure as hell remember the guy who dropped a smooth 50.

Buckets are important, but I also knew that half the respect you earned was determined by who you scored on. I didn’t want anybody saying I could only score on chumps. So during games, I targeted the guys who were the most respected. And people noticed.

“Yooooooo, you hear about how Homicide did ’em?!”

I didn’t care about the final score. What I wanted was people whispering about me when I got to the court, and screaming about me by the time I left.

Slowly but surely, I started making a name for myself, and the offers started rolling in from professional teams. Now mind you, they were bullshit offers, but that didn’t phase me. I mean if you’re living out of a garbage can, but that’s all you’re offered, what are you going to do? You make it work. At the same time, I knew I still needed to establish my rep in NYC. So I started splitting my time between whatever country would have me and the playground courts around the city. I’d be in Brazil during the fall, Stockholm in the spring, and then get right on back to New York to scratch names off my list.

Now at this time streetball was really starting to blow up. They were even showing our games on NBA TV. So because of that I was getting a lot more exposure. That’s a good thing.

Here’s some real easy playground math for you: Exposure = Money.

Eventually I got a tryout with a team in China. Killed that. And then the offer they gave me wasn’t any bullshit. It was the best payday I’d ever seen. It felt like I was really doing this. But, of course I ended up getting injured and had to come home for surgery. The timing of that just made me pissed as much as anything. Just when I thought I was getting over the hump. Then I’m sitting on my couch one day while recovering from surgery, thumbing through a spring issue of Streetball magazine (O.K., I’m a magazine guy). I was going page by page, and I could see that they were giving love to a lot of people — a loooot of people I had already busted — but not me. I kept flipping pages, and then I just started nodding my head.

A’ight.

That was what sparked what’s now known as the Summer of Homicide. I was fuckin’ done. I wasn’t chancing it anymore. I was finishing the job. Nobody would talk about ball in New York without bringing up my name. I averaged 40 at every tournament. And these were baaaad buckets. If any NBA player came in front of me hoping for an offseason workout, I destroyed their ass like, This my court motherfucker!

Ron Artest was the reigning defensive player of the year.

I gave him 27 on my way to earning MVP of the EBC tournament at Rucker Park.

I destroyed everybody.

And get this: My performance at EBC earned me an invite to an NBA training camp with the Toronto Raptors. That’s unheard of. The guys who go from the playground to the NBA were big stars in college. My reputation came entirely from playground basketball. I made it to the last cut before I was released. And I was pissed, man. I still am. That was the year kobe put 81on them. I could have seen that shit!

But just being there — having an NBA team see potential in me — enabled me to get a better agent, which resulted in better job opportunities. I don’t dwell on not making it to the League.

Because I know where I started. And now this game has taken me further than I ever could have dreamed.

All these years later, I still hit up the playground from time to time. If you’re around the city during the summer and have a handle, try coming out to Harlem.

Who knows, you could be my next victim.

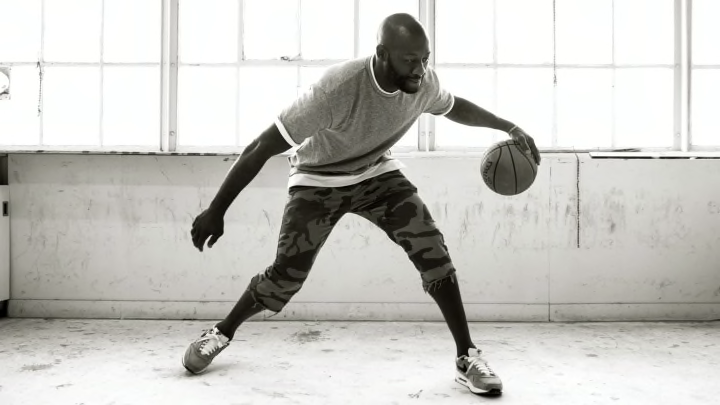

At 38, Corey (Homicide) Williams is still ballin’ all around the world. You can follow along his journey on his Instagram @thepatientwolf.nyc.