Body Blow

I thought the pills would make it better. You know, I’m a man, and men are proud and stubborn. We don’t go running to the doctor when something’s wrong. We let it play out a little bit. But if we do go to the doctor, and all he does is give us some pills and sends us on our way, it just confirms what we think we already knew.

It’s not that bad. I’ll be fine.

I was 22-1 in my pro boxing career with a world middleweight title in my sights, and I remember thinking, I’m 24 years old. I’m a world-class athlete. I’m healthy. I’m in shape. Ain’t nothing gonna stop me.

It started in March, 2011. I was on a USO tour in Iraq. We visited troops in Kuwait and a few other cities, and it was an amazing experience. I was having a great time, but something was happening with my left leg. There wasn’t any pain at all — it just felt fuzzy. You know when your leg falls asleep and it feels like you’re just dragging around a dead leg? That’s what it was like. Pins and needles. Only instead of shaking it off and my leg tingling back to life, it just got worse. It got so bad I had to leave the tour and head back to the States. I could barely walk.

The doctor said it was a pinched nerve, gave me some pills and told me everything would be OK. So I took the pills and went on with my life.

It was a good life, too. I was living with my girlfriend and my beautiful son in a penthouse apartment in Park Slope, a nice neighborhood in Brooklyn, New York. I was driving a brand new Camaro SS, and that was back when the Camaro was hot, back when it first came out. I was killing it inside the ring and I was doing well financially. I’d come a long way from that kid who grew up down the road in the rough neighborhood of Brownsville. Everything was going better than I could have ever imagined.

Except my leg wasn’t getting any better. I started using a cane. Soon after, I was using a walker. Can you imagine, me, a 24-year-old professional boxer, using a walker? Bright green tennis balls on the feet and everything.

I was taking the pills, just like the doctor said, but it just kept getting worse. I had no idea what was really going on inside my body.

*

“Do you know a boxer who lives here?”

I wasn’t picking up my phone. My godmother, Dorothea Perry, was pleading with the doorman to let her upstairs. The night before, I drove home — I don’t know why I was driving, I couldn’t even walk — and I left my cell phone in my car. I didn’t have a landline, and there’s no way I was going downstairs to get it if I didn’t have to. Not in my condition.

The doorman stood pat. That’s his job. He finally let her up when she explained who I was and what condition I was in. I don’t even know how she remembered where I lived. She’d only been there once. I think God sent her, because that morning, when I tried to get out of bed, I completely collapsed. I heard her knock at the door and I literally had to pull my body across the apartment with my arms to reach the door. I couldn’t move my legs. When she walked in and saw me, she started crying. She took me directly to the hospital, where a neurologist told me it was bad. Really bad.

An MRI showed that a handball-sized tumor had wrapped itself around my spine. It was blocking the signal from my brain from getting to my legs, which was causing the temporary paralysis. Now, I’m not a doctor, so at this point, I still don’t know what the hell is going on. I’m thinking I can just take some new pills — and it’ll just go away. My mindset was simple: How long before I get back into the ring?

That was on a Friday. On Saturday, they told me I had to have immediate surgery. The tumor was growing fast. If I didn’t remove it, I would probably die.

You have 12 thoracic vertebrae in your spine. My tumor stretched from my T-4 to my T-9. That’s the entire middle of my back — half of my spine. The doctors told me I would probably never fight again. There was a strong possibility that I would never walk again. All I could think about was the possible end of my boxing career.

The whole world just stopped turning. I remember this sinking feeling, like my body suddenly got really heavy. I just lost it. Not for one second do you think you’ll become a victim of cancer. Especially at 24 years old.

Osteosarcoma. Bone cancer. That’s what I had. Bone cancer. It’s one of those rare cancers you don’t really hear about. The surgery was a success, and they were able to remove most of the tumor. But there were still traces, so I had to undergo radiation to hopefully finish it off.

Radiation was the worst feeling ever. I felt groggy. My appetite went away completely. I was always moody — always sick. I threw up a lot. It was horrible. I’ve never experienced anything like it. But that wasn’t even the worst part.

Remember when I said I was doing well financially? Well, that’s not completely true. I had possessions. I had money, but I hadn’t managed it well. I was young and irresponsible. I wasn’t investing my money, I was spending it. I had people in my corner telling me to do the right things with my money — bringing me different investment ideas and business plans — but I didn’t want to do that. I wanted to be the young kid with all the money. I was going to the ATM almost every day and taking out at least $200 just for the day. Like every day. That money was there to spend, so I spent it.

When you’re on top of the world — making money and living the fast life — there’s an invincibility factor. It’s always a false sense of invincibility, but I felt it. I was on a roll, and I didn’t see how anything could stop my flow.

But cancer did.

You always hear people who’ve battled cancer talk about how it ravages your body. And it does. It breaks you down. But they don’t talk about what it does to the rest of your life. What it does to your livelihood. What it does to your bank account.

Part of my financial irresponsibility was the fact that I didn’t have health insurance. I was already about to get hit with huge hospital bills, but I didn’t know how I was going to pay for radiation and any further treatment I might need, until my godmother found out about an experimental type of radiation for which they were taking special cases — heard about it on the radio, of all places. I qualified, so she signed me up. And I was lucky. I was one of the special cases they chose. I didn’t even need any insurance. My godmother had come to my rescue. Again.

Still, when I was suffering through radiation, everything else kind of went downhill for me, too. The bills piled up. I lost the penthouse. I lost the car. My bank account vanished. My son was two years old at the time, and he and I moved back into my mom’s apartment in Brownsville — the place I’d literally fought so hard to escape. My son slept in my childhood bedroom while I slept on my mom’s couch. My weight blew up to 225 pounds and my body was wrecked. It seemed like everything I had worked for and achieved was gone.

There are a lot of reasons someone would want to get out of Brownsville, but not a lot of people get out. My oldest brother was still there, in and out of the streets, police always behind him. While my son and I were living at my mom’s, there would be times when the police would rush the house at two, three, four o’clock in the morning looking for my brother. You heard loud music throughout the night. Gunshots. Drug dealers inside the building doing deals and junkies using drugs. Things I never wanted my son to see.

Don’t get me wrong. I love Brownsville. That’s where I’m from. It’s beautiful in its own respect, but there’s an ugly side to it. There’s jealousy and envy. Having to protect yourself going in and out of your own house. Those are just the challenges you face being in the hood.

That motivated me more than anything. More than cancer. I was one of the lucky ones who got out of Brownsville, and I didn’t want my son to be a product of where I was born. I didn’t know how long we’d be there, but I wanted to get out as soon as we could. That was one of the most depressing times of my life. I got out once. I knew I would get out again.

Any parent knows, you’d do anything for your kid. So giving up wasn’t an option. I had to provide. And the way I looked at it — if I’m gonna battle back for anything, why should my goals change? Aim high, right? I still wanted to fulfill my dream. I wanted to become a champion. I wanted to be a boxing superstar. If I was going to battle back, that’s where I was going, and if I got there, everything else would take care of itself. I wasn’t going to settle for anything less just because I had cancer.

When I completed my radiation, the doctors told me to stay out of the boxing gym. “Boxing’s over,” they said. “Don’t worry about boxing. Just go to therapy.”

But I didn’t listen. I went straight to gym.

I was a swollen 225 pounds walking into the gym with a cane, hitting the bags with a back brace on. I could barely make it 30 minutes, but that’s how badly I wanted to be there. Those 30 minutes eventually turned into an hour. Then more. My legs were coming back. I was proving all the doctors wrong. And I started to really think, Maybe I can do this …

I guess I wore my doctors down, because eventually they said, “We don’t recommend continuing with boxing, but if that’s what you want to do, go ahead.”

*

It was early 2012 and I was reading the newspaper when I saw an article about the Barclays Center, which was set to open that fall. I made that my timeframe. If I was going to return to the ring, what better place than right here in Brooklyn?

Getting back into boxing shape was one of the hardest physical challenges I’ve ever faced. I had to get my strength back. I had to increase my stamina. I had to learn to take a punch again. When you’re taking punches, the spine absorbs a lot of that shock, whether it’s a jab or a body shot. After what my spine had been through, it took a while to get back to the point where I could take a punch.

On October 20, 2012 — 17 months and two days after I was diagnosed with that rare form of bone cancer — I stepped back into the ring at the Barclays Center to fight Josh Luteran.

He didn’t make it out of the first round. Just 1:13 in, it was over. Knockout.

I was back.

And I‘ve been rolling ever since. I’ve won all seven of my fights since coming back, six by knockout. And along the way, I reached the goal I set long before cancer almost took my boxing career away from me: I won the middleweight world championship. It felt incredible to finally reach that goal, but there was something else that made it even sweeter: I became the first cancer survivor to win a boxing world championship.

As I revived my boxing career, everything else started to fall into place, too. I’m able once again to give my son the life I want him to have. We got out of Brownsville, but I still go back frequently to work with the children and the people there. I’m able to do motivational speaking all over the world and do so many positive things with my life because of my journey and the battles I’ve fought. Without cancer, I would have never had some of these opportunities, and I wouldn’t be the man I am today. I’m a better father and a better friend. I’m smarter financially — no more reckless runs to the ATM.

When I was in eighth grade growing up in Brownsville, there was this bully. He was bullying kids all throughout the year, and one day, I guess it was my turn to get bullied. But I stood up for myself. I fought back, and we got in trouble for fighting. Later, I found out that same bully was going down to the local gym to take boxing classes. So I thought, OK, I can go down to the boxing gym and get revenge the right way. Not do it in the streets. Not get in trouble by the principal or our parents.

When I walked into that boxing gym, it was love at first sight. I was 14 years old, and for the first time, I felt like I belonged. I fell in love with the sport. I needed to be inside a gym. Boxing became my savior — it was my means to stay out of the streets and to eventually get out of Brownsville.

I ended up boxing that bully at the gym, and after I beat him, he never came back. I won, but without that bully, I would have never discovered boxing. Life’s mysterious like that.

Cancer was a lot like that bully. If I hadn’t fought that fight, I wouldn’t be the man I am today. Fighting cancer taught me more than I ever could have imagined, but I’ve beaten it. And I’m hoping it — just like that bully — will never bother me again.

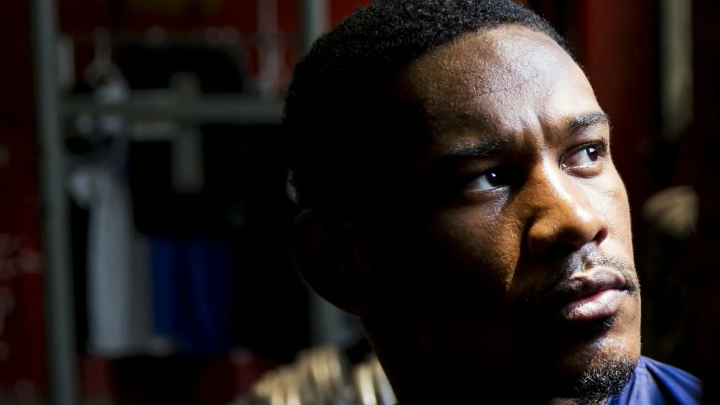

Daniel Jacobs is the founder of the Get in the Ring Foundation, which is dedicated to fighting childhood cancer, obesity and bullying. He’s currently 29-1 and will defend his WBA middleweight world title on August 1st against Sergio Mora at the Barclays Center in Brooklyn.