The Autograph

During my rookie year in the NFL, I met a teenage boy named Justin. He was a big Ole Miss fan, and a big fan of mine. He had cancer. His head was bald from chemotherapy. He had been going through a really tough time.

I was on a trip back to Mississippi visiting a Children’s Hospital with my dad. I guess Justin didn’t find out we were coming until right before we got there, because he asked me for an autograph, and he had a marker, but he didn’t have anything for me to sign. No paper, no football, no poster.

So he asked me to sign his head.

I looked around the room, thinking, Should I? Is this weird?

The hospital room was small. There were cameras, plus my dad and some hospital staff in there with us. It was the first time anybody had requested I sign a part of their body, so I didn’t know how to handle it.

Should I?

But Justin was adamant. He wasn’t going to be denied.

So I signed his head.

He was fired up. He was really excited about it.

It was a special moment for him — and for me.

When I was playing at Ole Miss, we took a team visit to a Children’s Hospital. That was the first time I experienced kids like Justin. You hear about sick kids, and you know they’re out there, but you can’t understand the things so many kids go through on a daily basis — kids who are fighting cancer and other diseases — unless you physically see it. It’s eye-opening. And your first reaction is, It’s not fair.

I think back to my childhood, and it’s all good things. Laughs. Smiles. You wake up, go to school, have recess, have friends, play sports … there are no bad days. But for these kids, every day is a fight — a fight for their lives. And there’s nothing fun about it.

When you’re a kid, you tend not to realize how lucky you are. When I got to Ole Miss, that was really my first realization that I had a privileged upbringing. I started to learn about some of my teammates, a lot of whom came from nothing. Every week was a struggle for them growing up. They didn’t have enough money for food, or their parents worked multiple jobs, so they weren’t around. It wasn’t anything like those kids fighting cancer, but it also wasn’t anything like how my brothers and I had it.

I’d known about my dad’s childhood. My parents told us when we were growing up about how his family didn’t have much money when he was a kid, and how they struggled. But that’s dad. When you start hearing stories about guys your age who go to the same school you go to, and play the same game you play, and they’re coming from a place like that? It really puts it into perspective.

So if you’ve never seen what some of these kids at these children’s hospitals go through every day — the battles they fight — it’s hard to put it into the proper context. It’s hard to fully understand.

That first time I walked through the hospital as a college student, I could feel a tugging at my heart: How do I help them? I’m not a doctor. I can’t heal them. What could I possibly do?

And it was kids like Justin who made me realize that one thing I could do is lift their spirits and get them to smile. Get them to have a good day. Without the means to do anything more, that was something, at least. So that’s what I did. And I learned that when you visit a kid who’s sick — one who’s really having a tough time or a rough day — and you get them to smile, it’s an incredible feeling. Or when maybe you can’t get them to smile that day because they’re shy or they’re just really down from their treatment, but you get that letter from their parents a few days later that says the kid couldn’t stop talking about the visit after you left.

It doesn’t heal them, but it helps.

And now, being a parent myself, those letters from parents mean even more.

Once I got to the NFL, I reached out to people to find out the best way I could help, in bigger ways. Really get involved. Which was when we teamed up the Blair E. Batson Children’s Hospital in Jackson, Miss. — the place where I met Justin — to build a Children’s Clinic. And over the course of just a few years, we raised almost $3 million to build the Eli Manning Children’s Clinics at the Batson Children’s Hospital.

It was the first step in moving past just brightening kids’ days and making them smile, to actually getting them healthy and back on their feet, back home to their families so they could enjoy life. Because at the end of the day, no matter what you do, it’s about tangible results. It’s about a measurable impact, no matter how difficult that can be to measure.

I remember visiting the construction site for the clinics back in 2008 after we won our first Super Bowl. Our dream of building the clinics was becoming a reality, and we wanted to see just how much progress we’d made.

Justin was there.

Four years after I signed his head while he fought cancer and endured chemotherapy and other treatments, there he was. Healthy. With a full head of hair. A cancer survivor.

He remembered the day I came to visit him, and he even had a picture from that day of me signing his bald head.

This time, he had a football for me to sign.

That’s why you work and work and work, and put in the time and effort. For the moments like that. The moments where you can see the results of the work that’s being done and that these kids are getting better and back to a normal life. There’s no better feeling than that.

And that’s what motivates you to find out who you can help next, and how.

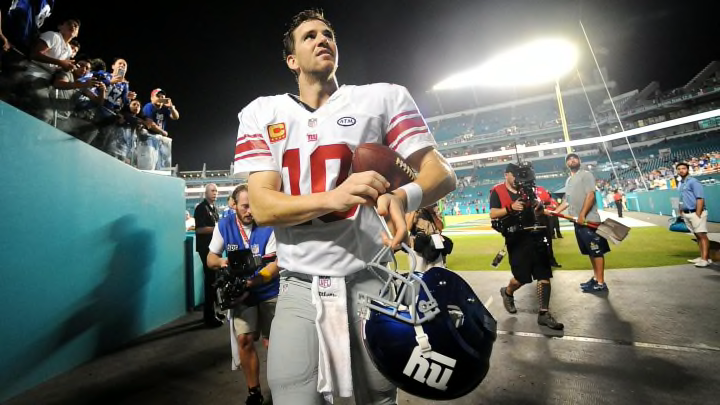

Eli Manning is a finalist for the 2015 Walter Payton NFL Man of the Year Award. The winner will be announced during the 5th Annual NFL Honors awards show, a two-hour primetime special airing nationally on Feb. 6, the night before Super Bowl 50, from 9-11 p.m. ET on CBS. For more information, visit nfl.com/manoftheyear.