People Say I Run Angry

I just kept running.

I didn’t know what else to do. I was just walking up to the gas station with three of my friends when a car pulled up in front of us. One of the dudes inside said something. I didn’t hear him. One of my friends said something back. I don’t remember what. The car sped off. We kept on walking. Then we saw the same car loop back around.

The lights cut off first. That’s when we started running.

Then came the gunshots.

We scattered. I was booking it down the sidewalk. Out of the four of us, the car chose to follow me. And the dudes inside just kept on shooting.

I broke off and jumped over a fence into somebody’s backyard. I juked my way through a bunch of kids’ toys and jumped another fence. I was trying to calculate how far I was from home when I realized … I couldn’t go home. These dudes were following me. And I didn’t want to lead them to my house.

So I just kept running.

I ran for about 10 blocks. One gear. Nonstop. A hundred miles an hour. Faster than I’ve ever run in my life. Just crashing through backyards and changing directions until I couldn’t hear any gunshots or car engines.

When I finally stopped, I had no idea where I was. I just remember it felt like all the air had been sucked out of my chest at once. Like I had been punched in the gut.

I know what it’s like to be scared. To be hungry. To have nothing in my future but uncertainty.

- Josh Jacobs

That was the first time I got shot at. I was in middle school. About 13 years old, if I remember it right. And I’ll be honest … I was scared, man.

But being scared isn’t even the worst part.

The worst is when you get used to it.

When you hear gunshots, and you don’t even run. When you see people fighting in the street, and you don’t even look twice. When the spotlight from a helicopter shines through your bedroom window, and you just pull the shades down.

Because it’s just another day in the life.

I was so relieved when I got home. Not only because I got there safe, but because I had a home to go to at all.

I grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma. When I was in the fourth grade, my parents split up, and I went to live with my pops. He had just moved out of his apartment. He’d had another one lined up, but it wasn’t ready yet. It was supposed to only take a couple of weeks, so we stayed with some relatives for a bit. But the apartment took longer than expected. When we had no family left to stay with and nowhere else to go, we slept in my dad’s Suburban.

I would shower in the locker rooms after football practice, then my pops would pick me up and drive around to look for a spot on the side of the road to park for the night. Somewhere out of the way. I would lie down in the back seat and he would be up front. I remember he had a gun, and whenever he laid his seat back at night, he would always keep it on his chest with his hand on it. Just in case.

If he ever slept, I didn’t see it. Every time I woke up — whether it was morning or the middle of the night — he was awake. Watching out. Protecting me.

We slept in that Suburban every night for maybe two weeks until the apartment was finally ready. We moved in, and a couple of months later, my dad won custody of my three brothers and my sister, and they moved in with us, too.

Then, my dad lost his job.

We eventually got kicked out of the apartment. Pops couldn’t pay, and the landlord had somebody else lined up who was willing to pay more anyway. So that was it for us. For the next two years or so, we basically lived out of our backpacks, hopping from motel to motel. Every now and then my dad would snag an apartment, but it wouldn’t last too long. And before we knew it, it was back to the motel.

On good days, we’d find a spot that had a continental breakfast where we could sneak enough fruit and bagels to last us a whole day. On bad days, we would eat rice and beans or ramen noodles. I was the king of white rice and ramen noodles, man. A five-star microwave chef. My dad used to buy them in big quantities so he could feed all of us. I’d cook for everybody.

Some nights, when the food supply was really thin, my dad wouldn’t eat. I would try to give him some of my food, but he wouldn’t let me.

I didn’t really understand it all at the time — the way we were living, the sacrifices my dad was making … none of it. I just never looked at our life as a struggle. To me, it was just life. It was all I knew.

But now, looking back on it all, I understand.

I understand how difficult it was for my dad. How frustrating it must have been. And he never took those frustrations out on us. Even on the worst nights, when we didn’t have enough food to eat or any clean clothes to wear to school the next day, we would still laugh together. We didn’t have game nights or movie nights. Pops used to have us sing. We’d write poetry. Freestyle rap while the others beatboxed. My older brothers would always draw. He wanted us to express ourselves. To engage with each other.

Even when our stomachs were empty, we would spend all night laughing together, as a family.

I remember one night, when money was at its tightest, my dad told me that if he went out on the street and sold drugs, we wouldn’t have to worry about money, or food, or a place to live anymore. There was plenty of money out there to be had.

But he said he would never do it, for two reasons. One, it was too risky. If he got arrested or sent to jail, there would be nobody to take care of us kids, and he might lose us. And that was out of the question.

And two … he said that the easy way out usually isn’t the right way. He said it’s hard work and perseverance that gets rewarded, not shortcuts.

That’s what he had been doing. Working hard. Persevering. Trying to do the right things, knowing — no … hoping — that everything would work out.

Then, the summer before I went into the eighth grade, pops landed a pretty steady job. We left the motels behind and moved into a house — the one in the rough part of town with the gunshots and the street fights and the helicopters. Food was still hard to come by. Money was still tight. Life was still a struggle.

But we finally had a place to call home.

Football wasn’t an escape. I didn’t play to take out my frustrations, or to cope, or to keep off the streets.

I played because I loved it.

By my junior year in high school, I knew I had potential. I thought I could be pretty good.

By my senior year, I knew I could be special.

My stats were so ridiculous that when my coach sent them in to the local newspaper each week, they wouldn’t even print them. They didn’t believe them. They thought my coach was padding my stats to make me look good. I sat back and watched as other kids with less impressive stats got their names in the paper and won all kinds of weekly awards.

I was getting nothing.

So my coach called up one of the reporters from the newspaper and told him to come down to McLain High School and watch me play in person. To come see for himself.

This was about halfway through my senior year. I was averaging around 300 rushing yards per game, but I still had no scholarship offers. I had zero stars on the recruiting websites.

I didn’t just want to show that reporter what he had been missing. I wanted to show everybody.

I scored the first touchdown of the game on a 65-yard run. By the end of the night, I had run for 455 yards and six touchdowns. And I did it all on just 22 carries.

It was the best game of my high school career.

My pops always preached that if you do the right things, everything else will work out. Control what you can control, and everything else will fall into place, he’d say.

So it was crazy to me that even after that huge game, it was still crickets on the recruiting front. By the end of the season, I had better stats than some of the dudes in my area getting scholarship offers. And we had basically played against the same competition.

“It’s like 12 minutes of straight touchdowns … how does he not have any offers?”

- Josh Jacobs

Just doing the right things obviously wasn’t working. I needed to do more.

But I didn’t know what else to do. I couldn’t afford football camps. My high school didn’t have a history of big-time recruits, so college coaches rarely came to visit. We just weren’t on their routes. And they don’t usually go out of their way to see just one guy.

Then my dad got a phone call from a random dude down in Texas. He said his name was G. Smith. He works with high school kids to help them get recruited. He had stumbled upon my highlight tape while he was checking out some other recruits, and he was so impressed that he tracked me down and reached out.

“This is one of the best highlight tapes I’ve ever seen,” he told my dad. “It’s like 12 minutes of straight touchdowns … how does he not have any offers?”

Coach Smith said he was going to help me get noticed. He told me to start a Twitter account and post my highlights. He would take it from there. And I don’t know what he did … but like a day or two after I started posting my highlights, my phone started ringing off the hook.

Wyoming, Missouri, New Mexico State, Purdue, Oklahoma … so many schools.

Some of those phone calls turned into scholarship offers.

That’s when I could finally breathe a sigh of relief. I had more than just some interest. I had actual offers. So no matter what, I was going to school somewhere — something not a lot of kids from my neighborhood get to do.

Wyoming was the first school to really show genuine interest in me. The first school to offer me. They were on me way before anybody else. Two weeks before signing day, it was basically a lock. I was going to Wyoming.

Then Alabama showed up.

Ask anyone I grew up with … Alabama was my favorite team. I had wanted to play there since middle school. So when they came into the fold, it was a wrap.

Everybody knows Alabama for being a football factory. For putting dudes in the NFL left and right. But I didn’t look at it that way. I saw it as an opportunity to play against the most elite competition in college football, and to get a quality education at the same time. Where I’m from, kids don’t get either of those opportunities. So that was all I was focused on. Getting to the NFL was the absolute furthest thing from my mind.

I honestly don’t think I even considered the NFL as a possibility until the SEC championship game last year against Georgia.

I had been sick the whole week. Flu-like symptoms. That weak kind of sick where your back aches and you don’t want to eat or stand up or even move.

I was at the tail end of it by the time the game came around, but I had missed a lot of practice time that week. I still couldn’t eat. I was dehydrated. I was in rough shape. The trainers tried to hold me out.

But I told them I was playing.

I got one IV before the game, two more during and one after. Every time I came to the sideline, it felt like I was dying of thirst and I had no wind. So they had the IVs and an oxygen mask right there waiting for me.

I only got eight carries in the game. But I ran for 83 yards and two touchdowns.

Enough to win MVP.

That was my Jordan Flu Game, man. I came out of that one knowing that if I could be in that kind of condition and not just fight through it, but still ball out … on that big of a stage, against a great defense like Georgia’s … then I have what it takes to play at the next level.

And if the Georgia game got me thinking about the NFL for the first time, the Oklahoma game basically punched my ticket. It felt like every time I touched the ball in that game, something special happened.

My favorite play — I think everybody’s favorite play — was when I ran over the safety on my way to the end zone.

The thing I loved most about that play is what happened after. Because the next few guys who tried to tackle me … they were easy targets, man. They were so worried about getting bulldozed that they were lunging at me. So I could lower the shoulder like I was gonna try and run them over, then hit them with a juke, and they’d go flying.

I love setting dudes up like that. It’s a chess game for me. I want to keep the defense guessing. Keep them off balance.

And I think that Oklahoma game is proof that I’m versatile enough to do that.

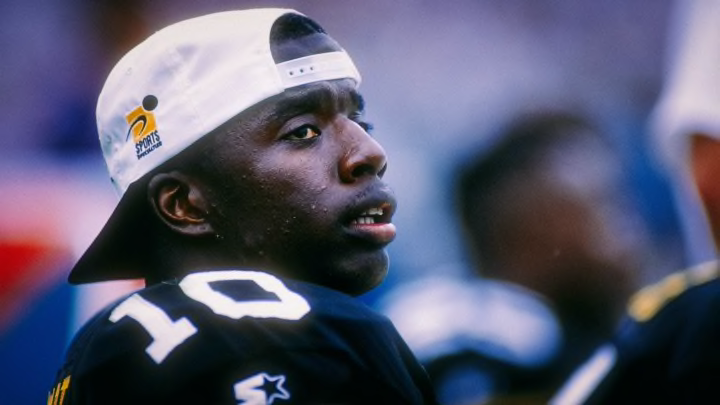

People say I run angry.

I don’t know. I guess I do. But I honestly don’t think it’s about how I run. It’s about why I do it, and who I do it for.

I run for my pops, the man who sacrificed so much and worked so hard to provide for me and educate me. I run for my three-year-old son, Braxton, so he can have a father he’s proud of, like I’m proud of mine. I run for my sister and my three brothers. I run for my teammates and my coaches. I run for everybody who has ever supported me, anyone who’s ever doubted me, and for anyone out there living on white rice and ramen noodles. I run for anyone who’s in a tough situation and feels like it’s never going to end — that there’s no light at the end of the tunnel.

I run to show them that there is.

Then, when I’m totally spent — when I’m on my last leg and I have absolutely nothing left to give … I dig even deeper.

And I run for me.

Because I love it.

Because it’s what I do.

That’s the kind of player you’re going to get if you draft me. Someone who loves the game of football. A hard worker who’s totally dedicated to the team, and to winning. You’ll get a fresh, healthy back, because I split carries at Alabama. They didn’t use me up. So I’m a low-mileage guy who’s ready to run up the odometer and shoulder the load.

But most of all, you’ll get a player who is very appreciative.

I’m never going to forget the nights spent in the back of that Suburban. I’ll never forget the motels. The gunshots. The helicopters. I know what it’s like to be scared. To be hungry. To have nothing in my future but uncertainty.

So I’m never going to take the privilege of playing in the NFL for granted. I’m going to come in and sacrifice whatever is necessary to succeed. I’m gonna hustle. I’m gonna put the work in and do the right things, like my pops always said.

Everything else will fall into place.