Beyond the Ring

I was in the stands with a fake ID, deep into my third beer, waiting to watch a heavyweight fight at a fairgrounds in Iowa that was hosting a fight night. One of the main event’s fighters was a no-show. The promoter walked into the cage with the fighter and said his opponent needed a challenger. He was the hometown guy and the crowd was ready for a fight. These were the old-school days of MMA — that kind of thing would never happen today. But it wasn’t that strange back then.

I looked over at my buddy who was sitting next to me.

“I think I’m going to fight tonight.” I told him.

I chugged the rest of my beer and raised my hand.

It wasn’t like I had no credentials. I won two national titles in wrestling my senior year in high school, but I had to give it up when I hurt my elbow during my brief college career. (More on my elbow injury later, because it plays a larger role in this story than you’d think.) Ever since I picked up my first UFC videotape at a flea market when I was 13, I thought MMA was the most beautiful sport out there. Back when I was a kid, mixed martial arts was advertised as this brutal sport, but I could see the art behind it. I still think MMA is the closest thing to a human chess match.

So I’m at the fairgrounds, a little tipsy, and suddenly I had to get ready to fight in a real MMA fight. Two times before, I had been in the corner for one of my guys when he couldn’t fight and I had taken his place. But I was definitely a novice.

And not to mention, I was wearing jeans and a button-down shirt, the outfit I came to the fair in. I had a pair of wrestling shorts and shoes in my truck. Someone had an unboiled mouthpiece, so I had to really keep my mouth clenched the whole time. This part’s pretty gross, but you need a cup when you fight, so I had to borrow this sweaty jockstrap and cup from a light heavyweight who had fought earlier in the night. Don’t worry, I wore it outside of my boxers.

It was my shortest fight ever. The guy was a wrestler, so I knew he was going to come out and immediately try to take me down. I saw him changing levels and I threw this huge uppercut at the exact right moment. It rocked him, and I followed up with a barrage of punches. He went down in 18 seconds.

Those first few fights were really just about being in the right place at the right time. It’s pretty hard to break into MMA, because just getting fights and having the other guy show up is a challenge. I was lucky. Around my sixth or seventh fight, I started to train seriously. Before I knew it, the UFC asked me to be on its reality show, The Ultimate Fighter, on Spike TV. I was the youngest guy there. Twenty-two years old.

Now back to that elbow injury. Before I got into fighting, I had that wrestling injury. I started taking pills for the pain, and I got hooked immediately. After every fight I ever had, I would go on a one-to-three week drug binge. Oxycontin had a grip on me, but I would always piggyback with other drugs. I would smoke weed with it, I would drink with it. Whatever I could get my hands on.

I had a doctor in Iowa who would give me 100 pills at a time because he thought he was the only guy I was going to. He knew that I had a back injury, that I had chipped a bone in my neck, and that I had an arm injury, so he would give them to me for 45-day periods. He would always tell me to come see him the next time I was in Iowa. I would always make sure to go back to Iowa. I had a guy in Colorado. I had a guy in Dallas-Fort Worth, where my family lived. So I was getting 100 in Iowa, 60 in Colorado, 45 in Texas. I would say I was going on training trips, but I was really just making an excuse to stop at all those places.

I went into the reality-show competition thinking I could win. I was one of the top choices, and the coaches told me they were picking me to win the whole thing, but I ended up losing two fights that could have gone either way. During that period, my immaturity and selfishness compounded. I’d snuck pills into the house, and with each loss, I spiraled further into addiction.

I was a sore loser. I didn’t know how to lose, or how to handle it. Fighting was what I did. It was my significance, it was my identity and it was my purpose. If I lost, I was a loser, and used drugs to cover the pain. If I won, I was a champion, and used drugs to celebrate.

At first, no one could see my addiction. You get pretty good at keeping it close to the chest. What I was supposed to be doing was training with Grudge, a team and gym in Colorado. I was supposed to be one of Shane Carwin’s main training partners as he was preparing to fight Brock Lesnar for the heavyweight title. But what really happened was a six-week drug binge.

During that whole time, I have maybe two or three memories. I was taking pills, ecstasy, cocaine, shrooms, acid — whatever I had access to. I was bouncing from drug house to drug house.

One time, a guy I didn’t recognize woke me up because he thought I was ODing. He was holding the back of my head and telling me to drink water. I remember crushing the bottle in one gulp. Maybe half of it went in my mouth. I had never been more thirsty in my life. A heat wave washed over my body, and then chills right after it. I was terrified in that moment. I didn’t even know who the guy was.

He said, “Who am I? Justin, you’ve been staying at my place for two weeks now, eating my food, sleeping on my couch, using my drugs. Who am I?”

I got out of the house and realized I was past Keystone out in Summit County, way up in the mountains. I had an eight-minute voicemail on my phone. It was my buddy, whom I had taken over for in my first-ever MMA fight when he had a staph infection. One of my best buddies in the world. He told me I had missed his wedding. I was supposed to be the best man. I could only make it through about 10 seconds of the voicemail.

I hitchhiked and caught a ride with a trucker back to Denver. I went straight back to drugs. I had hurt one of my best friends, and I couldn’t deal with the pain. When I showed back up at the gym, the coach called me into his office and said I was off the team.

“You have to go get your life right,” he said.

My childhood dream had turned into a nightmare. My mom finally discovered my drug addiction during a surprise visit to my Denver apartment. I wasn’t around, but all my paraphernalia was. She found a close friend of the family, and he hunted me down and told me he had a plan to get me healthy. I thought it was going to be a drug rehab treatment center, but he told me it was a faith-based approach.

Alarm bells went off in my head right away. I grew up in Texas, so Christianity had been all around me my whole life. I was, to put it one way, skeptical. I was mostly exposed to the types of people who said that every bad decision you made — getting a tattoo, drinking alcohol, going swimming with girls, even wearing shorts — meant you were going to hell. I even went to a church camp where they tried to cast the demons out of me. I think there’s a quote from Gandhi that was pretty accurate: “I like your Christ … Your Christians are so unlike your Christ.”

Over two weeks, though, he talked me into it. He told me these were real people with real problems dealing with a real God who gives real solutions.

Even in agreeing to go, drugs were still in my life. I brought with me an abundance of pills, THC drops and edibles. I figured I was going to meet a bunch of judgmental Christians who were going to tell me I was a bad dude.

The opposite was true. I got there and there were 35 guys that were all genuine and genuinely interested in what was happening in my life. I thought I had it bad. They were sharing junk from their lives that was just eye-opening. They were being transparent — almost uncomfortably transparent. They talked about their fears, emotions, addictions and more — all with really radical honesty.

They were rallying around each other — and I was on the outskirts watching. I had never seen anything like it. For the first three days, I was still using. I was closed off to it all. Finally, the next day, I opened up.

If you’re not a person of faith, I can understand how you might also be skeptical reading this. But it was a very personal moment. Nobody could ever force me to doubt that moment in my life. I had to look deeply inside myself for the first time.

I realized I wasn’t meant to be a drug addict. I realized that my identity and purpose wasn’t wrapped up in being a fighter — that I was more than that. That there were bigger, better ways I could use my life. In that moment, the best way to describe it is that God loved the hell out of me. I had drugs in my pocket when I got on my knees and prayed. That wasn’t something they asked me to do. It was something I felt I needed to do.

I fought in the cage twice more after the retreat. The first time, I wasn’t using. But the second time, I fell back into drugs. It freaked me out, so I decided to leave fighting. At this point, I had no idea of what to do with my life. It was the beginning of a five-year hiatus from fighting.

If you don’t already think my story is crazy, you might start to here. The best way I can preface it is this: Back when I was at the Olympic Education Center, the fighters would see a sports psychologist. He would tell us to visualize in your head the match you were going to fight, going over it in perfect detail 100 times before it ever happened. The idea is that you would imagine it so many times that it would happen as you pictured it.

A few months after the retreat, I was at a prayer meeting. I had an offer to fight in Japan with a great promoter and a great opponent, but I felt like I wasn’t ready yet. I was praying, and I had a vision. I know that probably sounds weird to most of you, but it was exactly like what used to happen at the Olympic Education Center. I saw myself in a jungle with a massive amount of trees, and I was walking on a trail. I heard drums and this really distinct singing. I came to a village, and there were people everywhere with their ribs poking out. I knew they were sick and starving and didn’t have clean water. I knew they were hated by their neighbors. I was flooded with emotion. To this day, I’ve never come close to crying like that. I left a puddle of tears.

I felt crazy and I had no idea what was happening. Later, I told a guy who had been at the prayer meeting about it, and he was like, “Those are the Pygmies.” I had no idea what that meant. He said, “It’s a group of people in Central Africa. There’s a war going on and they’re being killed right now. I’m going there on an aid mission in four weeks. You should come along.”

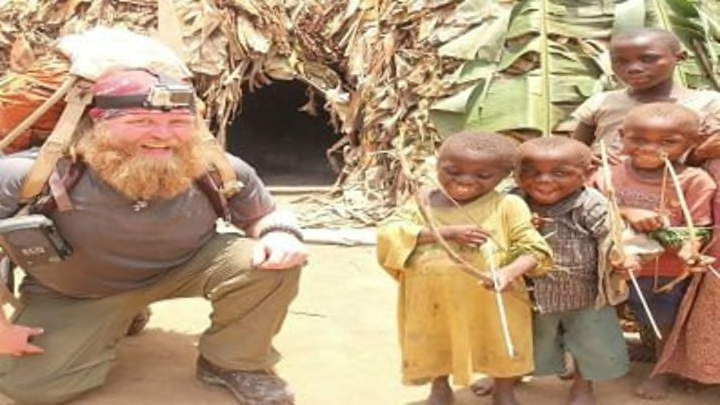

I decided to go — and 100 percent of the vision came true. Walking up to the village we visited, I heard the drumming and the distinct singing. I saw the sickness and hunger. The Pygmy tribes in Central Africa are a historically exploited people. Back in the early 1900s, the Bronx Zoo put a Congolese Mbuti Pygmy on display in the monkey house. Today, many of the surrounding tribes still view them as subhuman. They will take their land, use them as slaves and refuse them hospital treatment. Some rebel groups in the area even believe that if they kill, cook and eat a Pygmy before they go into battle, they’ll be bulletproof.

That first trip really wrecked me. I felt so helpless. I almost felt teased and taunted, because I didn’t think I was going there and be a hero or anything. But I still wanted to help. All I could think was how small I was, and how little of a difference I could actually make. I swore I’d never return to the Congo again.

Still, I couldn’t get the Pygmies out of my head.

I would say I didn’t get 100 percent committed until my second trip. A boy I had known died from one of the water-borne diseases that was wreaking havoc through the jungle while I was there. I helped dig his grave and bought the coffin. Later, I found out that the pills that could’ve saved his life cost about $1 and the shot that could’ve cured the disease cost $3. Meanwhile, the boy’s casket had cost $45.

His mom had tried to take him to the nearby hospital, but they had refused him treatment, saying he was too dirty to go in. She told them she wouldn’t take him inside, but just asked for the medicine. They asked for money. She told them that she worked as a slave and didn’t have any money. They said, “If you don’t have any money, you can’t have any medicine.”

She went back to her village of 100 people and begged. They worked and slaved to get the money and eventually were able to get the equivalent of about $3.50. So they came back to the hospital with the money, two dozen eggs, a chicken, a bag of charcoal and some firewood. The hospital staff said they weren’t going to waste their medicine on a “Pygmy animal.” People back home never believe me when I say this, but the Pygmies really are treated like animals.

Before I went on that second trip, I wrote down a list of four things I needed to do before I could attempt to help them: live with, listen to, learn from and finally, know how to love the Pymgy people. I had to get eye-to-eye with them and understand their culture, their needs and their lives. You have to actually build a relationship, mutual respect and friendship with them. You have to include them in the development that’s going to be done.

Many NGOs have gone into Pymgy communities with a solution already in their minds, refusing to actually adapt to the Pygmies’ needs. If you actually live with the Pygmies, you can learn from them and be able to figure out the best strategies to help them. I wanted to be a listener before I could be a doer.

My Pygmy friends call me Efeosa, which means “The Man Who Loves Us.” After the boy’s funeral, they gave me a second name, Mbuti MangBo. It means “The Big Pygmy.” I’ve spent the past five years of my life away from fighting spending as much time as I can in the Congo, helping my Pygmy family. I started a non-profit called Fight for the Forgotten, which recently joined up with the incredible foundation Water4.

When we see a problem, we want to look at it like a martial arts fighter … in a peaceful way. If we see the opening and opportunity, we develop a strategy and attack the problem head on, shifting to address changing aspects. While our priority now is water, the first project was focused on land. Water-borne diseases are the main cause of death, but without land, we couldn’t build wells for the Pygmy communities. We worked with a local college called the University of Shalom in Bunia to negotiate land transfers and we ended up being able to buy 2,470 acres of land for Pygmy tribes. Now, we work with Water4 to drill wells, which provide access to clean water for the first time in these areas. We’ve already drilled 25 wells.

We’re also starting agricultural projects to replant 3,500 trees in deforested areas and to instill safer agricultural practices. We’ve planted 250 banana trees and have helped the Pygmies start to cultivate corn, beans, potatoes, cassava and more. Our end goal is sustainability and to give the Pygmy people complete ownership of the projects, and we employ 17 local Congoloese nationals.

The first year I was away, the desire to return to fighting haunted me. The next four, though, I knew I didn’t have to fight in order to be happy. Over the last year, the idea of returning to fighting has crept back in. I met with the President of Bellator, Scott Coker, a couple times to discuss it.

I know how this story might come off to some people — a white guy with a drug problem finds himself and goes to Africa.

It’s so much more than that.

When I was younger, I only thought about myself. My drug addiction was all about myself. My identity was as a fighter and an addict. That’s all that mattered to me. Over the past five years, I became part of something bigger than myself.

On Friday, August 28, I will be back in the ring at Bellator 141. My win bonus will be going to my Pygmy family — a family that has become as real to me as my blood family. For the rest of my career, any win bonus I ever receive will go to land, water and food initiatives for them. I know that I can fight again because I’m not fighting for myself anymore. I’m fighting for them.

Learn more about Justin’s work in Central Africa at fightfortheforgotten.com