What You Don’t Know About: Being A Tight End

Have you ever been bull-rushed by an NFL defensive end?

It makes you ask yourself some tough questions.

Like, “Why am I doing this right now?” and “How can I make it stop?”

The first time I was on the business end of a bull rush was when I was a junior in college, and it’s something I’ll never forget.

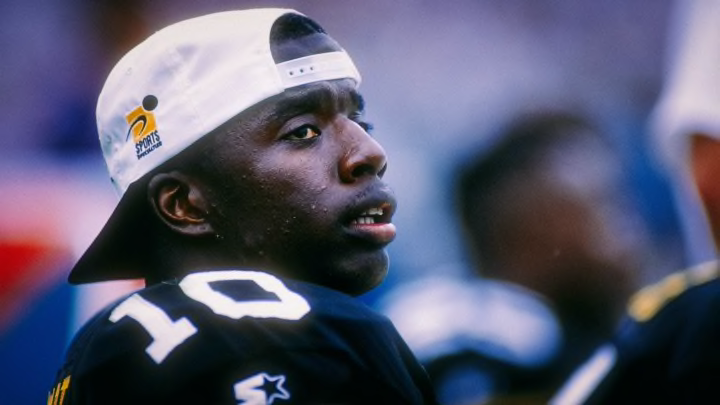

I had played quarterback my entire life up until that point. I was always the best athlete on the teams I played on, so it made sense to put me at the position where I had the ball in my hands on every play. Despite that, most of the schools recruiting me out of high school wanted me to play tight end. It made sense given my size and speed, but I was confident that quarterback was my natural position. I actually chose Cincinnati because it was one of the few schools willing to give me a shot at QB. But in the back of my mind I always thought that if all of those other schools were right and I was meant to be a tight end, it wouldn’t be too difficult to make the switch. I mean, I was tall and fast, with decent hands. How hard could it be?

Connor Barwin gave me the answer to that question pretty early on.

It’s really damn hard.

Most people know Connor as a defensive end for the Eagles, but when I was at the University of Cincinnati, he was my teammate. As a junior I determined the best chance I had to make it to the next level was to figure out how to play tight end.. Not long after I made that decision, I found myself lined up across from Connor in a blocking drill during my first practice in full pads. It was the first time I had ever really tried to block someone – as a quarterback, I’d never really ever participated in contact drills

Not surprisingly, I got my ass kicked.

Connor came off the ball, extended his arms and proceeded to just walk me right back. He could have walked me all the way across campus if he had wanted to — I was toast. I don’t think I’ve ever felt that helpless before. At the time, I didn’t understand how to gain leverage, how to shoot my hands or how to keep my balance. But beyond that, I didn’t stand a chance because mentally, I still wasn’t a tight end.

What I didn’t know then that I understand now, in my fourth year with the Kansas City Chiefs, is that being a tight end doesn’t really have much to do with being a great athlete. What’s much more important than your athletic ability is your mindset. Because ultimately, your job as a tight end is going to be to perform against somebody who’s a better athlete than you in some capacity. You have to block linemen who are stronger than you, and fake out defensive backs who are quicker than you. To do that, you almost have to trick yourself into thinking you’re better than you are. If your mind isn’t right, your body doesn’t stand a damn chance.

After getting my ass handed to me in practice a few times, I really started hitting the weights. It became clear that I needed to get much stronger if I was going to do this. I think early on it was important that I didn’t let the learning process really discourage me. Even when I was getting beat every day, I would stay positive by telling myself stuff like Listen, I’m every bit as good as this guy across from me. The thing is, you are every bit of what you think of yourself. If you think you can improve, it’ll happen.

Not only was it important for me to get stronger, but I also needed to fundamentally change my approach to football. Quarterbacks need to keep their emotions in check so that they can always be thinking clearly. But if you want to be a tight end, you need some juice. You’re grinding it out in the trenches and catching slants in the no-fly zone. You have to have an edge out there. So as I made the transition, I decided I wanted to have the mindset of Jeremy Shockey. Jeremy was just a bad dude. He wasn’t an athlete, he was a tight end. He was a football player. That’s the type of player you want as your teammate and that was the type of player I wanted to be.

I realized early on that there’s no perfect way to play tight end. Actually that’s not true. Jason Witten is perfect. When Witten’s on the field, every step is right. Every route is crisp. Everything catchable is grabbed. Every single ball, every single play. Jason Witten is a model of consistency. But in the likely scenario that you are not Jason Witten, there are certain ways to improve at the position so you can at least get a bit closer to being like him (but still not like him because nobody is as good as Jason Witten). The first step towards that is to become as proficient at blocking as you are at catching the ball.

To be a good run blocker – particularly when you’re learning the skill from scratch — you need to have a certain mentality. I’m 6′ 5″ and 250 pounds, and I’m regularly matched up against guys who are 6′ 7″ and 280 or 290. But even when you are matched up against someone closer to your size, like an outside linebacker, the job doesn’t get any easier. I play in the same division as Khalil Mack, Melvin Ingram and Von Miller. I see each of those guys twice a year, and they know all of our plays. So essentially my job is to figure out a way to block a smart guy who’s also an athletic freak capable of squatting a semitruck. These guys are used to being blocked by offensive linemen who weigh 300-plus pounds, so when they see me lined up across from them, I know they’re licking their chops. They’re thinking sack.

But even when I’m at a clear disadvantage, I always believe I can take the guy across from me. Even when in the back of my head I know there is not a chance in the world, I just try to get after it. Because here’s the thing about football (and probably many things in life): Nine times out of 10, if you just come off the ball and hit whatever challenge you’re facing in the mouth, that’s at least a start. Nine times out of 10, you’re gonna surprise ’em if you come off the ball and hit ’em in the mouth.

Blocking is part physicality and part physics. You have to be the lower man and get your hands inside to control your opponent’s mass. If you have short footwork, tight hands and if you play low, you can hold your own. Then there are other little tricks to level the playing field. I’ve been taught that every player’s body has what are called cylinders, which are areas that are naturally a bit weaker. Sometimes a guy has one shoulder that’s a little weaker or he might be a little slower in his hips. So that’s why a lot of times blocking comes down to technique as much as strength — not just hitting hard but hitting precisely. There are certain points on the body you can target that will make even the strongest guy feel a little weak.

It’s really important to become a capable blocker, because that’s the best way to also make yourself a credible threat in the passing game. There are some plays where you start off blocking and then flare to an open space on the field to get the ball. The only way it’s going to work though is if the defense buys that you’re blocking that play. We call it giving the guy a little bit of Hollywood — a little Hollywood in the route, a little Hollywood in the play-action. You have to sell them on the idea that you are doing something else. Just give ‘em a shot in the chest, then give’em little Hollywood and slide into that open spot on the field.

When it works well, it’s kind of surreal. One of the most bizarre things you can see while playing in the NFL is open field in front of you. It’s shocking, honestly. You want to move, but half the time, you give’em a little Hollywood and then suddenly see all this green in front of you and it’s like Oh shit, what happened here? If you ever are fortunate enough to experience an open field in front of you as a tight end – and honestly, that’s something not many guys at this position ever get to experience in the NFL – the one thing that you know for certain is that there are people faster than you who are right behind you and want you to fumble the ball.

The biggest leap between the NFL and college football is the speed. That’s something you hear often. But I think there’s more to it than just the speed of the players – there’s also the speed with which you have to process information around you. In college, I would basically get a signal from the sideline and would run my route based on that. In the NFL, what I do on a given play is determined by how I read the defense as much as anything else.

When I walk up to the line, I immediately look for where the other team’s safeties are. I have my eyes on them at all times because those are the guys that are gonna determine where the play is gonna go. If a safety rolls down this way, we’ll target an area of the field he’s leaving open. The one thing every NFL defense has in common is that it’s sound. No matter where guys move on the field, every single foot of space will be accounted for. So for an offense it’s like determining a pattern — a strategic pattern. If they bring a certain blitz, then all right, now I know where the holes are.

The challenge comes in deeply understanding your assignment and having the entire offense on the same page without needing to speak. Plays are deconstructed from the safeties, to the ’backers, then down to the line. If the defense changes at the last second — for example, if I see a safety coming down strong toward the line — I have to know that it means the defensive end closest to him is going inside, which means I can’t go to the inside release and shoot across the field because that leaves our blocking scheme vulnerable. My job is immediately knowing that situation and understanding what my quarterback expects me to do in reaction to it. That’s why we practice … and practice … and practice.

Want to know the other reason I keep an eye on what the safety is doing during a play?

Well, my first NFL game was against the Titans, and I came out of the gate hot. Made my first catch. Incredible feeling, really. Then, two plays later it looked like I was about to make my second catch. I was running a slant across the middle of the field. I knew that was my assignment. You know who else knew that was my assignement? Bernard Pollard, one of the hardest hitting safeties in the NFL. As soon as I caught the ball, I was looking upfield and Bernard absolutely leveled me. Put his helmet right in my sternum. I was flat on my back and the ball popped out. Fortunately it was just ruled an incompletion rather than a fumble, but I got the point. You have to really get rocked like that a few times to develop the senses you need to avoid the big shots. Once you really get popped, you don’t want it to happen again. I mean, it will, but you don’t want it to.

But that really is the nature of this sport and this position. No matter what your experience level or how great you are, you’re going to take a shot at some point. That’s inevitable. What matters is how you take it. Do you stay down or do you get back up and pop ‘em in the mouth on the next play. That’s what defines you as a player. More than anything else, that’s what makes a great tight end.