Why I'm Going Back to Indian Wells

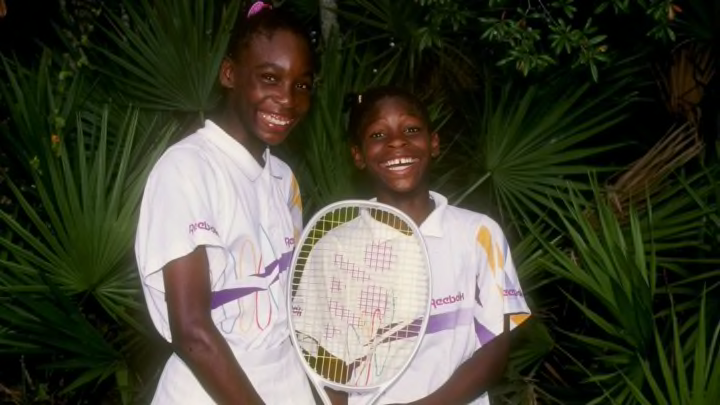

There is just something about being the big sister.

When you’re the big sister, you’re first — always, always first.

Sometimes, that’s a perk. Being the big sister means that you’re the first to earn your driver’s license. It means you’re the first to go out on a date. You’re the first to be allowed to stay up late, or home alone.

It means you’re the first to grow up.

In my family’s case, it also meant that I was the first to turn pro as a tennis player. The first to play in an official WTA tournament. The first to play against a world No. 1. The first to beat a top 10 player, to play in a Grand Slam, to make the final of a Grand Slam.

And, of course, it meant that I was the first to become famous.

I was the first to have articles written about me. The first to have autographs requested of me. The first to have TV specials produced about me, awards given out to me, shoes named after me.

I was the first to be known by my first name only.

Venus. Just Venus.

I was the big sister. I had to be first.

I’m proud of that.

Sometimes, though, being the big sister is a responsibility.

For me, being the big sister meant that, when I made my professional debut, I was the only player on tour who looked like me. I was the only player with my skin color, with my hair, with my background, with my style.

Being the big sister meant that, when I became world No. 1 in 2002, I wasn’t just world No. 1. I was also the first black American woman to reach No. 1. And it meant that I had to carry with me the importance of what I had accomplished. And I was honored to do that.

Being the big sister meant that, when my little sister made her professional debut, I became a lot of new things to her — her colleague, her competitor, her business partner, her doubles partner. But I was still, first and foremost, the one thing I had always been: her family. I was her protector — her first line of defense against outside forces. And I cherished that.

Being the big sister … I didn’t take that responsibility lightly. I knew what she was going through — debuting as a professional tennis player, growing up in front of a camera, entering public life as a young black teenager — and I knew how hard that could be. And I knew how much I would have loved to have had a big sister on tour during my first year, and how much pride I took in the knowledge that my little sister had me.

Serena always has me.

But I’ve never had to tell her. Being the big sister means that nothing ever has to be said out loud. It’s unspoken, and understood:

You can do it. I did it, so you can do it. Just follow my lead.

Being the big sister means that you don’t just pave the way.

You show the way.

Most of all, though, being the big sister is a bond. And a bond has no age, and no direction; it’s not defined by who’s older, or younger, or who has which responsibilities, or which perks. A bond is never about who’s first.

A bond is about strength.

Being someone’s big sister means being strong for them.

And sometimes “being strong” means, yes, being strong. But other times — more often than not — it really just means being there. It means being there, when needed, no matter what.

And that — above all else — is what being the big sister means to me.

It means being there.

It means being there for Serena.

When Serena decided to play Indian Wells last year, I was so proud of her. She hadn’t set foot onto the grounds since our 2001 tournament — neither of us had.

Leading up to her decision, Serena told me that she had been reading a lot about Nelson Mandela. She had been learning about him, thinking about him — processing all of these complex questions about his journey and his principles.

About forgiveness.

When Serena becomes passionate about something, you can see her eyes light up about it. And I could tell right away that learning about Mr. Mandela was something that she was taking very seriously. And so it didn’t surprise me at all when, soon after, she brought up the idea that there might be this unique opportunity for her at Indian Wells — to not just learn from Mr. Mandela’s experiences, but to apply what she had learned.

I was proud of Serena for so many reasons: for the sense of self she displayed in tackling our complicated history at Indian Wells; for making her decision with such conviction; for conveying her decision with such grace and clarity; and, of course, for playing with that exact same grace and clarity.

And I knew that I was going to be there for Serena, no matter what — because that’s what big sisters do. They’re there.

I watched her and I cheered for her.

And I was so, so proud.

But as proud as I was, the truth is, my personal feelings hadn’t changed: I didn’t think that playing Indian Wells again was something I’d ever do.

On the court, Serena is much more emotional than I am — and everyone sees her competitive side a lot more than they see mine. But that doesn’t mean I’m not emotional, and that doesn’t mean I’m not competitive. I think I’m just … more instinctively quiet about it. Not as a conscious thing. It’s just my natural way.

And honestly, in my own way, I might even be the more competitive of the two of us. I think that Serena’s ability to lay everything bare on the court allows her to work through her emotions more easily. For me, though, it can be a more conflicted process. My quietness lets me stew a little in my thoughts. And once I feel a certain way about something, my competitiveness can make me a little slower to come around to the other side.

And that’s how it was for me with Indian Wells.

On one hand, my memories of what happened in 2001 are still so vivid.

I remember my quarterfinal match, against Elena Dementieva, like it was yesterday: 6–0, 6–3, a really good win over a really good player. I remember the pain of my knee injury, and how badly I wanted to play in the semis against Serena — before finally accepting that I wouldn’t be able to. I remember the accusations toward me and my sister and our father. I remember the crowd’s reaction, as I walked to my seat, during Serena’s match in the final. And I remember how I couldn’t understand why thousands of people would be acting this way — to a 19-year-old and a 20-year-old, trying their best.

There are certain things where, if you go through them at a certain age, you simply don’t forget them.

But on the other hand, when I think about it now, all of these years later — it’s less my memory of the events that happened, and more my memory of how I felt when they happened, that has stuck with me.

I remember the hurt I felt. I remember my confusion and disappointment and anger. I remember how the coverage of it at the time didn’t seem concerned with me and Serena, as people, at all — but rather only with the story itself. And with the version of the story that would get the most attention, regardless of the truth. I remember feeling that I had been wronged, and that I had done nothing wrong. I remember feeling that I had unfairly gotten the brunt of the blame for a bad situation.

And I remember leaving Indian Wells in 2001 feeling like I wasn’t welcome there.

Not feeling welcome somewhere is a hard memory to let go of — at any age. At 20? It’s almost impossible. And so that’s what I did. I held onto it.

But then I saw Serena.

And it was in that moment, seeing Serena welcomed with open arms last year at Indian Wells, that I think I fully and truly realized what being the big sister means.

It means that, for all of the things I did first, and all of the times when I paved the way for Serena, the thing I can be most proud of is this time.

When Serena paved the way for me.

I’ll be playing Indian Wells this year — 15 years after my last appearance, and one year after Serena’s. As the tournament draws nearer, I’m looking more and more forward to it. I’m looking forward to the amazing California grounds. I’m looking forward to the top-notch WTA competition. And I’m looking forward to the fans — who played such an important role in helping to make last year so special.

But most of all, I’m looking forward to playing tennis.

Sounds simple — I know. But after almost 30 years of playing this sport, I’ve learned something. I’ve learned that, no matter what happens, or happened … or where you are, or where you’ve been … at the end of the day: tennis is tennis. It’s always, always tennis. And there’s nothing better.

Who taught me that?

Actually, funny story — it was the greatest player in the world.

I’m her big sister.