The Day Our Lives Were Split

PARA LEER EN ESPAÑOL, HAZ CLICK AQUÍ .

Having a twin brother isn’t like having a regular brother. If you have a regular brother, one will be older, so he will kind of lead the other. You’ll be in different classes in school, which means you’ll have different friends, different routines, all that. But when you have a twin brother, it’s almost as if you’re living the same life.

Especially if you both want to become professional footballers.

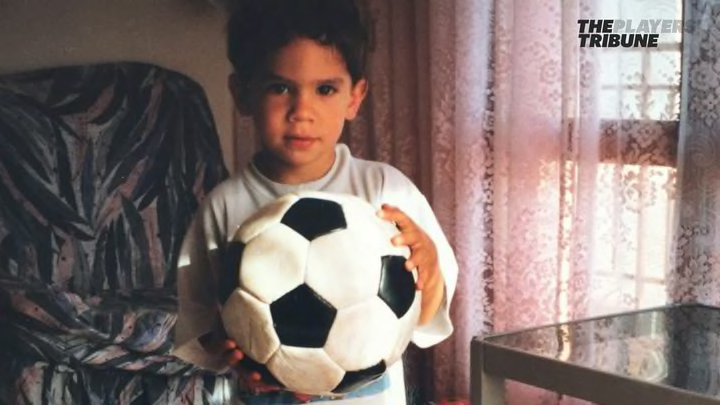

Almost from the moment Èric and I were born, 27 years ago, we were together 24 hours a day. We ate at the same times, we went to the same school, we had the same friends … we even shared a bunk bed because our room was too small for two single beds. We had a poster of Frank and Ronald de Boer, who were also twins and played for Barcelona. We were huge Barça fans, because we grew up in a village near Barcelona named Sant Jaume dels Domenys. Maybe we could become like the De Boer brothers?

We knew we had the genes, because our father had played football in the third division. We played in the streets, in our bedroom — and even out on our balcony, which was about one square meter! I look back at that period as a happy time.

But sadly, it wasn’t always as idyllic as it sounds.

You know those twins who don’t just look alike, but act the same way too? Well, Èric and I weren’t like that. We’ve talked about it with our parents, and we still wonder how two brothers can be raised in the same way, in the same place and at the same time — and yet be so different.

It’s extreme. Éric was always an introvert: shy, contained, reserved. I was more exuberant. He was the clever one in school, a real thinker. I was more impulsive, the one who just dived into things.

Maybe it was because of these differences, I don’t know … but we fought a lot. We had a love-hate relationship. There was jealousy, because each had skills that the other wished he had. On the surface, it just seemed like a healthy rivalry, because brothers tend to be competitive, right? But there were spells where it wasn’t healthy at all.

Yet at the same time, he was my brother. I loved him, and that’s what made it so complicated. I wanted to beat him, yet when he did well, I felt I ought to be happy too. And our lives were so similar anyway that when something good happened to him, it usually happened to me too. For instance, when we were eight years old, we had a two-week trial at Espanyol, one of the best youth academies in Spain … and the club accepted us. Then we began playing games against Barça. Two years later, Barça signed us both.

Our lives changed. We were 10 — we couldn’t just move to the big city on our own — so the club would send a taxi to drive us the 75 kilometers from our village to Barcelona, which took an hour each way. We’d do our homework in the car, then strap on our boots and run onto the pitch. I felt it was the start of the journey we had always dreamed about.

I thought, This is it. We really are going to become like the De Boer brothers.

The dreaming was the easy part, of course. The pressure at Barça … man, it’s different to anywhere else. You have coaches who watch you like hawks. They notice every detail. Does this kid have the temperament to make it? How’s his pace? Can he control it with his weaker foot? When you make a mistake, you can almost sense the coaches and coordinators scribbling stuff on a notepad.

“Marc gave the ball away. Monday, afternoon session, 18:13. File under: UNFORGIVABLE ERRORS!”

And that’s not even the scariest part. Because you also know that, even if they’re just a little unhappy with you, they’ll bring in someone else. This is the Barça academy — every kid in the world wants to play there. You’d see these talents come not just from the whole of Spain, but from Mexico, Israel, Brazil, Germany, wherever. And you’d think: If I don’t do well, next year they’ll be here, and I’ll be gone.

Trust me, that’s pressure. Especially when you’re 10 years old. You don’t really have the maturity to deal with it. You’re living the life of a seasoned professional, yet you’re still a kid. And honestly, I don’t remember enjoying it much. I loved it when we got to train with the ball, or when I could play with my brother. But on a day-to-day basis, having to train hard and study to get good grades … well, I found it very difficult.

My brother being there made it even more complex. We trained together and played on the same team. Sometimes I’d be happy with a game I had played, but if he had spent it on the bench, I’d have mixed emotions. I wanted us both to do well. I don’t know if it was the pressure of playing for Barça that did it, but our rivalry grew. It became darker. Sometimes I even thought, Maybe my brother doesn’t like me?

It was a horrible thing to think about someone I had spent my whole life with. But if I was unsure if he liked me up to that point, something happened that I felt sure would make him dislike me afterwards. Over the previous year Èric had begun to grow a lot. Parts of his body couldn’t keep up, so he suffered a lot of injuries. He also fell in love with a girl and, well, he lost a bit of focus. One day, at the end of the season, a coordinator at the club gathered my parents, my brother and I, and he told my brother: “We’re letting you go.”

But I would be kept on.

What can you do in moments like that? On the one hand, I was so happy; I would continue to play for Barça. But then I thought about Èric and about us. And I realized, Wow… this is it. It’s over.

In that single moment, our lives had been split. We weren’t going to do homework in the taxi together. We weren’t going to train or play together. We weren’t going to become like the De Boer brothers.

It was such a bittersweet feeling. It felt as if a part of me had been torn away.

I’ll never forget the car journey back home. The usual hour felt like a year. Nobody said anything. His dream had been crushed, but mine was still alive.

I thought, O.K., now he definitely doesn’t like me.

About two or three years later, Barça invited me to live at La Masia. That’s the name for the academy right by the Camp Nou stadium, where the big talents go to study and train full-time. Many of the homegrown Barça legends have passed through it, so it was a huge step for me. But it also meant that I had to leave my home, my family, my friends. And my brother.

I’ll never forget the day I left. Picture it: I’ve packed my bags, the car is waiting outside. I’m standing in the doorway, casting a final glance at my childhood home … and then I see Èric.

And I think, S***, it’s really happening … we’ve spent our whole lives together, and now I’m leaving.

And then my brother … well, he starts crying.

Actually, he’s sobbing. The tears are streaming down his face. But I don’t understand. Why is he crying if he doesn’t like me?

Then my mother tells me that Èric has spent the whole day crying, thinking about me leaving. And that’s when I understood that we were closer than I had ever realized. That deep down, we loved each other. We were brothers — of course we did.

Our relationship changed after that. Whenever I’d see him, he’d seem different. He had become more mature — more so than most kids his age. It was as if he had accepted that his dream wasn’t meant to be. And soon he began to be happy for me. He’d be like, “Hey, so I wasn’t able to do this, but my brother Marc, he did it. And you know what? His success is my success too.”

And he was right: Even without wanting to, he had made me better. Things began to go really well for me and, in 2009, I made my first-team debut for Barça against Manchester City in the Joan Gamper Trophy, an annual preseason friendly at the Camp Nou. Yet the really big one was my debut in an official competition. I was 19, and we were playing away against Atlético Madrid in La Liga. That game felt … well, let’s just say it was more than a game. In fact, it was more than a title.

Because debuts are more personal than titles, you know? And it wasn’t special just because I was sharing a locker room with my idols. No, it also symbolized my rise to the top of the greatest club in the world. I had started out at a club from a village with little more than 1,000 inhabitants, then climbed step after step at Barça. I had endured tests, criticism and pressure, year after year after year. And now I had made it.

When I saw my parents afterwards, my mother was crying. My father was so happy. And my brother, I’m telling you, he was the proudest guy in the world.

I felt I had made that debut for all of us. My brother felt the same way too.

By the 2013–14 season I had established myself with the first team and begun playing for the Spanish national team. But then, for whatever reason, I started to become less important for Barça. And by the summer of 2016, I realized that if I wanted to continue to evolve and feel happy, I would probably have to leave. I’d have to get out of my comfort zone.

It’s strange — this should have been a horrible moment for me, leaving my childhood club.

But you know what? I was actually excited. Because I knew that a new adventure awaited me at Borussia Dortmund. I knew I had given the club everything. And I knew how much I had enjoyed being part of the team and winning lots of titles at Barça.

My year in Dortmund turned out to be eventful. I was playing well, growing and evolving, and our team reached the Champions League quarterfinals against Monaco. But on our way to the stadium for the first leg, in Dortmund, three bombs exploded right by the team bus. Luckily, only one person got hurt. As it happened, though, that person was me. A piece of shrapnel flew through the window and hit my right wrist, damaging the bone so badly that I had to be rushed to hospital for an operation.

Incredibly, I was back playing at the Westfalenstadion just a month later, in front of 80,000 fans. They were shouting my name, because they knew what I had been through. On top of that, we scored a late penalty to win the match, the one that clinched our spot in the Champions League. After the game … well, I broke down in tears. It was a mixture of many feelings: contentment, achievement, joy. I had returned to do what I love the most, having overcome the shock of what happened and the nightmares that followed.

And yet that wasn’t even the highlight of the season. Just a week later, I started the final of the German Cup. Dortmund hadn’t won a big trophy in five years, so this was huge. When we beat Eintracht Frankfurt 2–1, the fans went wild.

As for me, I realized that I had gone from the hospital bed to the podium in six weeks. It was the comeback of my life.

When I lifted the trophy, I did it with so much pride that I felt I was about to burst.

Today, every time I wake up, I think about the people I love, how fortunate I am to have them and how much they helped me when I was injured. I think about how proud I am of the family I have formed with my wife, who I feel privileged to have as my life companion, and how proud I am of our two precious daughters. I never lose sight of how lucky I am to have played for Barça, Dortmund, and now, since January, Real Betis – whose love and affection make me feel privileged to play there.

I value all these things much more now, not just because everything could have ended, but because I know how quickly the dream I’m living now can, for whatever reason, be taken away.

Just like it was taken away from my brother.

Thankfully, Èric is living another dream now. Back in our village, he’s a coordinator for a youth system that connects footballers from several towns, and he loves it. He lives for teaching kids about tactics, technique — and about life and values.

Our relationship isn’t so complex anymore. There is no rivalry, only mutual admiration. We respect each other, support each other and love each other.

After all, he is my brother. My best friend.