Ana

Content warning: This essay contains strong language about suicide, suicidal thoughts, eating disorders and mental health.

I always had an exact schedule. A plan. For every single thing I put in my body.

In the mornings, I’d wake up and think it all through in my head.

O.K., I’m not going to eat breakfast. Then I’ll go to school, and my mum will pick me up for lunch. (I had to have supervised lunches. I couldn’t be trusted.) But I won’t eat much of lunch, I’ll just eat around the edges of it. Most of the time when I came home for a lunch break, I would get angry about the whole process. Whoever was picking me up that day would say, “You’re not eating…. Can’t you just eat?? Why don’t you just try this little thing?” Then I would just throw a tantrum and run upstairs to my room. So I never returned to school.

My change was drastic.

Within a month, I went from being a healthy, happy young girl who was living her dream — playing football with these amazing players every day, going to school and learning — to being a depressed and troubled young girl.

This started back when I was 13, playing club football. I had been called up to play for England that year, and I swear I blew it. I got injured, and it felt like my whole world just folded in on me. I hated myself. I thought I was worthless, so I just gave up. I couldn’t handle the feeling of failure and letting everyone down.

It wasn’t like I tried to fight whatever was happening to me. I didn’t try to eat. I just let it get worse and worse. I turned completely cold to anyone who tried to help. I said and did things that I will regret for the rest of my life, to protect my secret.

I remember one time I was in my bedroom, and my mum came to the door. She was having a go at me for not eating, as usual. And I said, “Will you just leave me the fuck alone?”

(I was 13!!!)

I didn’t even realize at the time what was coming out of my mouth. That’s not me. My mum is my role model. She’s literally my person. For me to say that, I was really low, and I was hurting.

But the truth is, I wished she was dead, so then I could just be alone.

I really said that to her. “Will you just die???”

I didn’t want to know that I was ill. If no one was watching me, it meant that I could be sly with what I did and not eat and keep getting away with it. I just didn’t want to get caught.

I would slam the door and lock myself in the room with a key, and I would sit there, and I’d hurt myself the whole evening. I’d scrape my wrists as hard as I could with my fingernails. I did everything possible to try and hurt myself.

My head was boiling, and I was screaming inside.

It was a parent’s worst nightmare. I was 13. I was supposed to be young and free. A kid. I should have been hanging out with my best friend, Charlotte, and playing football with my teammates. My mum and dad probably had all these dreams for my future. But it was like inside my head, one day, the music just … stopped. Almost like those ballerina music boxes, you know? Like how when you open them and a beautiful dancer spins around to the music and then when you close it, it all goes dark and silent. That’s what it felt like. Like one day, I had all this joy inside me, and the next moment, someone had turned my light out.

I remember how I’d be seething alone in my room, just really fuming. Mad at the world. At myself. At the voice inside my head.

That was the thing that was doing this to me, that voice.

You don’t deserve it.

You’re not good enough.

It was like somebody was telling me that, and I just kind of allowed them to talk to me.

The voice would say, It’s your fault. It’s your fault.

I don’t know why, but my brain would just tell me that I had to do something to myself as punishment. Like stop eating food. Or scratch up my wrist. Or…. There was a mirror in my room.

Sometimes when my head was really boiling, and I was at the height of one of my tantrums, it’d get too hot to handle. All these alarm bells would be going off like someone pulled the fire alarm in my head. Like all the lights were flashing on the dashboard at once. I just wanted to crawl out of my skin. To make it all stop.

So, I would run over to the mirror and smash my head against it until everything was black.

When I look at the story backwards, it’s like there were two different Mollys — the Molly before Holland, and the Molly after. That’s when everything changed. When the switch just … flipped.

At first I was on a high. I got called up to England for the first time in my life. It was massive. Actually, massive doesn’t even begin to cover it. That’s what we all sort of dreamed about, but I never thought I’d actually be like that, you know? Standing there, in that shirt, and singing the national anthem on the pitch.

But there I was getting on a plane to Holland, wearing the England tracksuit, flying to my first international camp.

My whole family came. My mum, my dad, my brother, my grandparents, they all flew to Holland to this game because it was obviously a huge moment. Even for my age group, the England under-15s team, you obviously don’t get to that level without making some sacrifices along the way, and your family, too. So, yeah, it was great. A Romford girl gets called up to play football for England.

So we fly there, the day before the match. And that evening we’re doing some light training.

I remember the feeling more than anything. I was running, and I guess I just overstretched my leg, and my hamstring just cramped up. I didn’t know if it was a pull or if it was torn or if it was a tendon issue. I didn’t know what it was back then. For me, it was just, I’m supposed to be living my dream right now, and I’ve fucked it.

I mean up to this point, I’ve never had an injury, and now I’m in Holland, and I’ve picked up an injury the day before the game.

If you can picture the lowest moment of your life, that’s where I was. Keep in mind, I’m 13. I’m just a kid. I didn’t know how to deal with that. I was spiraling, thinking like, Am I ever going to get this chance again?

“I couldn’t handle the feeling of failure and letting everyone down.”

- Molly Bartrip

I remember our physios helped me off the pitch. And the whole time, I’m not even really there anymore, you know? I’m watching the whole scene from outside of my body, like I’m in a nightmare.

The next night at the match, I wasn’t allowed in the changing room since I was an injured player. I remember having to sit in the stands with this scout that was kind of like a player liaison for the team. My parents were four or five rows behind me, and I wasn’t allowed to go and sit with them. It killed me that I couldn’t be with the girls, and I was watching every single one of them do what I wanted to do. I was jealous. This was literally my first competitive match against another country. I tried to put on a happy face for my family. But inside I was going mental.

And so, if you were to ask me today, the Molly after Holland, where it all started, I’d point at that and say, there. In the stands. Staring out blankly, past the match, past … everything.

That’s where things first went really, really wrong.

At that age you don’t have this complex vocabulary of emotions. You’re just happy, or you’re unhappy. (Or you’re pissed off.) After Holland, I knew that whatever I was feeling was extremely unhappy. Something inside of me was starting to eat me alive.

This went on for a couple of weeks. And then, the next England call-up was announced. It was against Ireland. And I wasn’t on it.

I remember thinking that this was my only chance to ever play international football. And I have just blown it by getting a silly little injury. I mean, I couldn’t have really changed it, but it still felt like it was all my fault. It’s all my fault. I thought I had to punish myself.

So that’s when I stopped eating. Unlike my selection for the England camp, eating was something I could control.

At first, I was pretty good at it. When you’re ill, you’re crafty. You do things that you don’t realize at the time are mad. But you think it’s pretty cool that you’re getting away with it.

I’d always eat with my mum and my brother at breakfast, so I knew I couldn’t get away with that one. (Dad was always the first to leave in the mornings — he works long hours.) But at school, I could throw my lunches away. And dinner was always quite small because I’d ask my parents to make only a small plate for me.

Then, it escalated. I started leaving earlier for school, so I wouldn’t have to have breakfast. (That’s two meals gone.) And I’d have a tiny dinner. And then it just went from pretty much eating nothing at dinner to chucking food away on my plate, right in front of my parents. No one really said anything at first — teenage girls go through phases and do weird stuff all the time. So, everything was fine, I thought. Everything’s normal.

But one day, I really messed up.

It was lunchtime, and my mum always made really good lunches. I love marmite. So it’d be like a marmite and cheese sandwich, which is like my favorite thing. (Yeah, I know — so English.) There’d be a pack of crisps and a cereal bar or something. A bit of fruit on the side. But for me that was like plenty. And I usually loved it.

But on this particular day, I did what I’d been doing for quite a bit now. I was sitting with my friends. And towards the end of lunch, I got up from the table with my food, and I walked across the cafeteria, and like it was nothing, I just threw it away.

I remember the day like it was yesterday.

I remember throwing my lunch away and one of my friends seeing me do it.

Damn, she’s caught me.

When I walked through the front door after school, my mum was waiting for me.

There’s that mother-daughter thing, you know, like they know you better than you know yourself.

I had no idea at the time, but earlier that day, someone had grassed on me to our head of year. And my head of year rung my mum and told her I’d thrown my lunch away. That’s why she was waiting there for me. She said, “You need to go somewhere. We need to get you sorted.” She pretty much dragged me by my hair to the doctor. Because I obviously refused. Denial was the whole thing. I’m like, I’m fine. I’m fine. I’m fine.

At the surgery, they did some tests — obviously height and weight and BMI. And they gave a couple of short questionnaires. And then the doctor came back with a diagnosis.

She told me I had anorexia nervosa.

I didn’t really know what that was. So, I was just like, “Alright.” I thought I was just over exercising, undereating. Then she said, “You’ve got to go see a counselor now, every week, and you’ve got to do a food diary.” And I was just like, What????

That was when I first thought, Something’s not right.

But I went. It’s not like I had a choice. And I hated every single minute of counseling because it made me realize more and more that I was really ill, and I didn’t want to know I was ill.

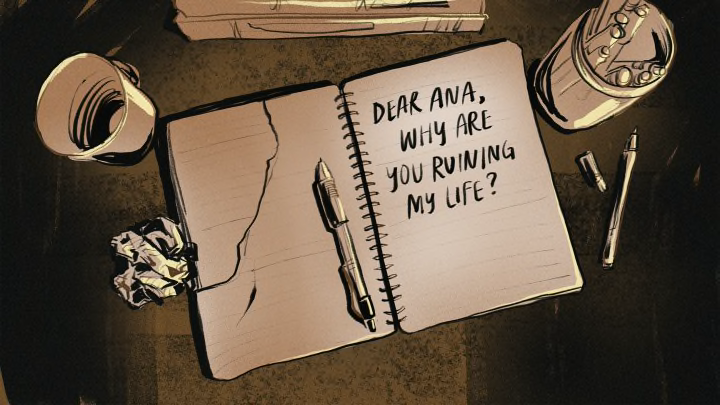

There was this one thing that got through to me, though. I remember one day I was talking with my counselor (or like not talking, I guess), and she said, “So this illness that’s in your head, that’s talking to you and telling you these things, do you reckon you could write a letter to it?”

“Write a letter to an illness, are you joking?”

She said, “Yeah, call it something.”

I was like, “Right, O.K.”

She said, “Let me just give you a name. Let’s call her Ana. Write a letter to her tonight and then come back to me next week, and we’ll see what you did.”

So, that night, as crazy as it sounds, I wrote a letter to the illness. And I discovered that writing was the only way I could talk to it. It was the only way I could describe exactly how I was feeling, and get out the anger inside me. It’s not like I could punch my shoulder or something. I couldn’t do anything to it, you know? So, I just wrote it all down. I wrote that I wanted her gone because with her, I wouldn’t be able to live my dream. I wouldn’t be able to succeed. Forget football, because those things come and go. If I kept on like this, I wouldn’t even be able to live.

Dear Ana, I wrote. Why are you ruining my life?

You keep talking to me, you keep telling me things, but I know deep down I shouldn’t be listening….

Why???

Once I was diagnosed, that’s when the supervised lunches started.

Sometimes it was my Nan who would pick me up from school, and that was great for me because I was able to work my way around my Nan, and I was malicious. I was horrible. I was nasty to my Nan, but she didn’t think anything of it. She knew I was sick.

I’d say, “Nan, can you go and get me a drink?” And when she’d leave the room, I’d quickly run down to the garden and throw my food in the bush. She’d have no idea. She’d talk to my mum and go, “Oh my God, Molly’s had a great day, and she’s eaten all of her food.” My mum would be like, “She doesn’t eat for me.” But my Nan would say, “No, no, no, I know she ate it.”

“Denial was the whole thing. I’m like, I’m fine. I’m fine. I’m fine.”

- Molly Bartrip

Then my mum would go down to the garden and find the food. So my mum was on me, and that’s probably why I was a little bit more extreme with her, but I still did it to others, too. My dad was there to support me and the family, but I was around my mum the most. She was pretty much the person that was there the whole time. My grandparents knew what was going on, and they would look after me, but they would never know what I was actually doing behind the scenes.

And then there’s my brother, Joe.

He’s four years younger than me, and he’s like my best mate.

Joe? He was like my masterpiece.

My mum would ask me to pick my brother up from school since it was on the way home from mine. So, I’d pick him up, and I’d have some cash, and I’d go to the local off-licence and say, “Can I have a pack of crisps and a pack of biscuits?”

I’d buy them for him to eat. He thought, “Oh my God, sick. My big sister’s buying me all this food. This is amazing.”

We’d get to the house, and my parents wouldn’t be in until later. So, we’d come home, and I’d sit there in the lounge, and I can still picture it to this day….

I’d sit there, and I’d watch him eat.

I’d watch him eat it.

A lot of people won’t understand this but.... It would make me feel good just to see him eating more than me.

He was 10 at the time. I look now, and I go, What the hell was I doing?

To this day, to be fair, we joke about it. He goes, “So you’re the reason I have to go to the gym every day now.” But back then, that was not a joke. That’s a really bad thing to do to your younger brother.

I’ve asked myself, Why on earth would I do that?

But then I suppose it’s like ticking boxes for the anorexia. It’s like you’ve done that one job. You know? Like out of the whole household, once I was eating the least, it was like, Right, O.K., job’s done for today. My dad ate more than me. My brother ate more than me. My mum ate more than me. It was like a successful day if I could make all that happen. That’s how it felt. Whenever other people would eat in front of me, I would feel better.

Because then, I’ve won.

Around that time, I was getting really bad. My mum found out about the snacks I was giving to my brother, and one day she said, “O.K., this is enough. You’re ruining your brother. Your dad’s not enjoying your company. You’re hurting them, Molly. So we’re going away for a bit.”

She took me to Southwold, which is in Suffolk, on the east coast of England. We had family friends who had a cottage there. We went away for five days.

When we got there my mum said, “You know what I’m going to do this week?”

She said, “I’m going to eat exactly the same as you.”

That was probably the worst thing anybody could have said to me at that time. My head went…. I was fuming. She was kind of cheery when she said it, just matter of fact. “I’m going to eat exactly the same.”

And she did. Literally to the point where if I had a strawberry and a half, that’s what she had. There was no budging whatsoever. It would be the same. Exact. Things. For a week she did that.

That was also the first time she took a picture of me when I was anorexic. I remember seeing the picture and thinking, That looks different from what I see in the mirror. That doesn’t make sense.

When I looked in the mirror, I thought I looked bigger. And now, I’m looking at the picture, and I can see bone. It was pretty much like my first wake-up call. (There were three.)

Like, Fuck! What am I doing? I do look ill there.

I made my mum delete the picture.

I did not allow my parents to take photos of me usually. The only ones that exist from that time are from when we went to America, actually. We went to Orlando and did all of the theme parks and stuff (like everybody does). And at one point, we were at Universal Studios, and we took a couple of family photos. I still have those pictures, and when you look at them, you can tell that my face and my shoulders are pretty gaunt. The hairs on my arms were thick. My teeth looked too big for my mouth. I was kind of yellowy. I was just ill. I had really bad liver function and if I’m honest, I didn’t have my period until I was 17, 18. That’s one of the side effects of anorexia.

I wasn’t just ruining my mind, I was ruining my body.

As crazy as it sounds, I was ill, but somehow, I still found the strength to keep playing football at a high level. I was playing for Arsenal, and they were the best women’s team at the time. But once I got diagnosed, I wasn’t allowed to train. When I was at my lowest weight, my body would’ve failed. I remember seeing a photo of the Arsenal team and telling my mum, “I’m never gonna wear that kit, am I?”

My mum was like, “You’re not playing, and you’re not training. You’re not doing anything.” I wasn’t allowed to. I actually don’t think I would have been physically able to do a two-minute run, if I’m honest. I had nothing in me. There was no energy in me whatsoever. I was just drained. So, I wasn’t playing, but I was fortunate that Arsenal was very supportive. They were incredible in the whole process. They made sure my mum updated them on my situation every single week.

I still remember the phone call. My mum called John Bayer, who was the director of the Centre of Excellence at that time and said, “Molly’s been diagnosed with anorexia nervosa. We can’t allow her to play right now. She has to be at home and get herself better before she can even attempt to step on the pitch again.”

I was sitting in the kitchen at the time hearing it. It was Reality Check no. 2.

You are ruining what you want right now. It’s not helping you.

You think you’re doing this for a good reason, but actually, what are you doing apart from killing yourself?

Literally. I had really bad liver function. That was probably the worst side effect. The doctor was really worried about that. I had reached the point where I was about to get tube fed.

I went to the hospital because my parents couldn’t cope anymore, and when they put me on the scales, that was when I was at my lowest (which I won’t say, because this shouldn’t be aspirational).

There were like little things that made me realize what I was doing to myself, and that was one of them.

Seeing those tubes being set up was the third and final reality check.

I think everyone knows that being tube fed is almost like you can’t fight your mind anymore. I didn’t have much knowledge about anorexia, but what I did know was that being tube fed was when you were on your last legs.

In my head I was like, No, I can fight this thing. I know I can.

I was so scared when I was on the bed. It seriously knocked some sense into me. At that moment, I really felt ill. And I remember my parents stepping out of the room, which also freaked me out, because then I really was alone.

When they started to get all the tubes ready, I pretty much kicked the nurse out of the way and was like, “No, I can’t do this.” They stopped. She told me that my BMI was so low that, “If it was one less, I would not allow you out of this hospital.”

I was lucky to get out of there, and as soon as I came back out, it wasn’t a light switch, but it was a process from there to recovery.

I wasn’t trying to fight this before. But I was trying now.

I was eating after about seven months, but I wasn’t eating normally. I was eating enough to survive — not enough to survive as an athlete, just enough to be a normal human being, doing a normal job. Kind of a sedentary lifestyle to be fair. Not really exercising, but I obviously went back into football once I started eating, and I was lucky my body would allow me to continue it.

For a year and a half, I couldn’t gain much weight. I was on protein shakes, I was on everything. About two years into my recovery, I was at a more healthy weight but I still had disordered eating, and then I can remember this moment five years later, when I was 19, when I knew that I was actually getting better. And that was the happiest day of my life.

It was the Domino’s.

See, my favorite food since I was a kid was bacon. But I’d told myself that I couldn’t eat anything that involved fat, so I hadn’t been able to eat bacon.

I remember I was with my teammates, and we ordered Domino’s one day after a game — a Texas barbecue pizza with bacon on it.

And the thing with anorexia is the guilty feeling after eating something like that. But I didn’t feel guilty one bit. And that was when I knew I could do it. It might be a long battle, but I knew I could fight this thing and lead a healthy and happy life.

I called my mum and I remember being like, “Mum, guess what? I just had a Texas barbecue pizza with bacon on it.” I was so excited.

And I can only imagine what a relief it was for everyone else.

That was like the icing on the cake, to be corny.

I wish that was the end of the story.

But I want to tell the full truth about mental illness. And the truth is, my issues went deeper and lasted longer than my eating disorder.

After my recovery, I had a good couple of years with football. I signed my first professional contract at 18 years old, which was what I dreamed of. So to get to that point was amazing for me.

Well, a few years into pro football, and I was still finding my feet. It wasn’t exactly going the way I expected it to. And I’ve always been a very fragile person from Day One. I really care what other people think of me. I always overthink the entire world. Plus, there were a few issues at home.

All I remember was my head turning, almost like before, and I started to feel really unhappy.

I was living in the team accommodations at the time, and one morning, everyone was getting ready to go, and I was still in bed. When one of the other girls checked up on me, I said I didn’t feel right. She told me to just make sure I told the physios and try and have a chill day, which I did. But I didn’t end up leaving my bedroom the whole day. I was just drained from it all. I genuinely thought I was under the weather or something. Like I had a cold.

Well, that one day stretched into a week. And then, I remember at the end of that week one of my friends came and sat on the end of my bed and asked me what was up. I just didn’t feel myself, I said. I was really sad, and I didn’t know why.

I remember ringing my mum and she was like, “Why don’t you come home?” So I went and called the team physio and said, “Look, I just need some time. I don’t know what’s wrong.” Then I went home, and I went to our family doctor.

And she was like, “Ha! You again?”

No, I’m joking. She asked me if I was alright and I told her I didn’t feel right. So she gave me these questionnaires to fill out. On the questionnaires, it was like, “Do you not want to leave your room? Do you want to hurt yourself? Are you having thoughts about not wanting to be alive?” And I was ticking every single box because I was feeling that way, but I didn’t actually know I was feeling that way until I read it.

I was diagnosed with severe depression and anxiety. And I was like, Well, brilliant. What do I do now?

After I got diagnosed, they signed me off for a couple of weeks from football. And at that time it got so bad that I did not leave my room, ever. I watched the whole of Grey’s Anatomy by the way, which — everybody knows how many seasons there are … it’s not just two!! Lol. I watched all of Grey’s. I was basically Meredith in my head.

I was eating, so it wasn’t anything related to food. But I started harming myself again, and I thought about dying a lot. I didn’t really know what the point of life was anymore. I’d see football on television. I used to watch my team on whatever channel it was at the time. But it didn’t make me want to go and play. And because I had obviously dealt with anorexia before, it was like, Why is God throwing another thing at me? I’m still drained from the last one.

I was put on antidepressants, which made everything a hell of a lot worse in the beginning. It made me realize that I didn’t want to be alive. There wasn’t any point. And keep in mind, I’m a professional footballer at the time. Even with the highs and lows, that’s still pretty incredible. But I didn’t even care. I was going through so much pain at the time that it wasn’t worth it to me anymore.

And I remember a moment that I will never, ever forget.

It was the 2017–2018 season, and I was playing for Reading. I was taking time off football, but I was still reaching out to my friends, who were my teammates and colleagues. And no one replied, which is like … when you’re dealing with any kind of mental health issue, you already think nobody cares. Especially with depression and anxiety, you feel alone. So for about a week, I would just be texting them, and they wouldn’t reply. And I was really confused.

Eventually one of the girls replied and explained, “We were brought into a meeting and told that we need to let you do this by yourself with your family.”

And that hurt. I was like, “What??? I need you though.”

I remember texting the manager and saying, “Please, can I come to a game? I just want to see my friends.”

So I went to the next game, and I had a really nice time. To be honest, I was very socially awkward. I had to sit in a certain part of the room, and I had hair ties on my wrists that I was fiddling with. The anxiety kicked in really early when I sat with them, but it was lovely to see everyone because I needed to. I stayed the night at my friend’s because I just wanted to be with people who I felt normal around.

Then the next morning, when I left her house, it was just like something hit me: I wanted to leave everything behind. And in my head it was like: This is the right time to do it, because it’s done.

I was on the M25, and I was thinking in my head, I’m just going to crash the car.

I’m going to speed into the central reservation, and I’m going to kill myself.

I was shaking so bad at the wheel that people were beeping me, and I was just swerving and swerving. In my head, I was spiraling.

And all I remember is slamming on the brakes, steering into the hard shoulder and sobbing. I tried to call my mum, but she didn’t answer. I tried to call my dad, and he didn’t answer. I tried to call my friends, none of them picked up. And at that point I was like, this is it. I’m just going to kill myself. But I was already pulled over, and I still had about 15, 20 minutes left in the journey. And somebody in my head was telling me to just get home. Somebody was telling me not to do it.

I got home, and when I walked inside, my phone started ringing.

Everyone I called was calling me back.

I mean, I had actually sent texts to my friends saying that I was going to die. And obviously, as soon as they’d seen it, they freaked out and were like, “What the hell? Are you O.K.? Are you alive?”

I was alive.

Yeah ... somehow, I was alive. A little voice spoke to me in my head, and told me to go home, and I was still here.

I know that a lot of people reading this are going to be shocked about me telling this story.

And that’s O.K. That’s kind of what I want.

I am a professional footballer. I play for Spurs. I’m healthy and happy. But I could just as easily not be here.

Everybody knows that when you’re ill, when you’re struggling with mental illness, you need everybody. You need as much support as you can get, whether you think you need it or not.

I never had friends from school, because of how much of my life I gave to football. So the friends that I had were my football friends. And they were taken away when I needed them the most.

They were told not to speak to me. And I still can’t understand that. I’m not bitter. But I just don’t understand.

That’s why I wanted to write this.

I’m sharing so much of myself for a reason. I know a lot of footballers deal with issues like eating disorders, or depression, or anxiety, because I can see it. It’s almost like a sixth sense that I have from going through it.

And if I’m being brutally honest, I don’t think the culture of football is fully equipped to deal with these issues among the players. We’ve made a lot of progress in the area of mental health, but there’s still more work to do.

"When you’re ill, when you’re struggling with mental illness, you need everybody. You need as much support as you can get, whether you think you need it or not.”

- Molly Bartrip

We’re at a moment now where we’re really trying to push women’s football for the next generation. We see it as part of the job, to keep promoting it and to keep doing what we can to make sure that women’s football gets to parity with the men’s game.

And getting there means acknowledging the elephant in the room when we need to and making mental health a big deal — not just a side project. I think, just from my own experience, it’s almost as if people need to see it to respond. Help is always reactionary. People aren’t trained to notice certain behaviors and be proactive. We need more awareness about triggers.

Once people realize the triggers, especially in sports, of people who are struggling with their mental health, that will make a huge difference. If we can get more staff, more players learning about the topic, then it’s not going to be a shock to their system when it happens. It’s also not going to be a shock to them if they’re the one going through it, because they’ve heard about other people who’ve gone through it, too. It’s not like, “Oh, you’re a freak, you’re a weirdo.” Which I think is what happens internally when we choose not to talk about difficult issues. Those things become stigmatized. It builds shame.

And shame is dangerous.

At Tottenham, I’ve been asked to be a wellbeing leader, to keep spreading awareness and to keep making sure it’s O.K. not to be O.K.

I’m not saying that I’m perfect, because I’m far from it. I think I’m always going to have my ups and downs because it’s pretty much in me now — and to be honest, that goes for my struggles with anorexia as well. But I’m doing really well, and I’m healthy. And I know that I can deal with everything a lot better.

I look at life now and think, playing football every day, doing what I do every day and loving what I do every day, is actually just a gift. I’m just going to try and make everybody proud.

Especially my mum — my person — who never gave up on me.

If I can do that, then my job is done.

And whatever happens after that … happens after that.

It’s funny, I’ve always wanted to make it. Become a professional. Play for England. Right now, I like where I am. I’ve found a home in Tottenham. I feel safe, appreciated and happy. I’ve got my friends and my family supporting me. We’re all so close because of everything we’ve been through. We just always move forward and go with the flow of life, I suppose.

And I know I’m only 25, but one thing I’ve learned in this life is that sometimes “making it,” means literally just … making it.

And the big accomplishment is just being alive.

And that’s O.K.

Actually, that’s more than O.K.

That’s a gift.

For support, resources and treatment options for yourself or a loved one who is struggling with an eating disorder:

United States residents: Please visit the National Eating Disorder Association or call their confidential helpline at (800) 931-2237.

United Kingdom residents: Please visit Beat Eating Disorders or call one of their confidential helplines in England, Wales, Scotland or Northern Ireland.

Hear more from Molly Bartrip on The Football Podcast by UEFA We Play Strong here.